10. Diffie-Hellman key exchange

In the previous sections, we discussed symmetric-key schemes such as block ciphers and MACs. For these schemes to work, we assumed that Alice and Bob both share a secret key that no one else knows. But how would they be able to exchange a secret key if they can only communicate through an insecure channel? It turns out there is a clever way to do it, first discovered by Whit Diffie and Martin Hellman in the 1970s.

The goal of Diffie-Hellman is usually to create an ephemeral key. An ephemeral key is used for some series of encryptions and decryptions and is discarded once it is no longer needed. Thus Diffie-Hellman is effectively a way for two parties to agree on a random value in the face of an eavesdropper.

10.1. Diffie-Hellman intuition

A useful analogy to gain some intuition about Diffie-Hellman key exchange is to think about colors. Alice and Bob want to both share a secret color of paint, but Eve can see any paint being exchanged between Alice and Bob. It doesn’t matter what the secret color is, as long as only Alice and Bob know it.

Alice and Bob each start by deciding on a secret color–for example, Alice generates amber and Bob generates blue. If Eve wasn’t present, Alice and Bob could just send their secret colors to each other and mix the two secret colors together to get the final color. However, since Eve can see any colors sent between Alice and Bob, they must somehow hide their colors when exchanging them.

To hide their secret colors, Alice and Bob agree on a publicly-known common paint color–in this example, green. They each take their secret color, mix it with the common paint color, and then send it over the insecure channel. Alice sends a green-amber mixture to Bob, and Bob sends a green-blue mixture to Alice. Here we’re assuming that given a paint mixture, Eve cannot separate the mixture into its original colors.

At this point, Alice and Bob have each other’s secret colors, mixed with the common color. All that’s left is to add their own secret. Alice receives the green-blue mixture from Bob and adds her secret amber to get green-blue-amber. Bob receives the green-amber mixture from Alice and adds his secret blue to get green-amber-blue. Alice and Bob now both have a shared secret color (green-amber-blue).

The only colors exchanged over the insecure channel were the secret mixtures green-amber and green-blue. Given green-amber, Eve would need to add blue to get the secret, but she doesn’t know Bob’s secret color, because it wasn’t sent over the channel, and she can’t separate the green-blue mixture. Eve could also try mixing the green-amber and green-blue mixtures, but you can imagine this wouldn’t result in exactly the same secret, since there would be too much green in the mix. The result would be more like green-amber-green-blue than green-amber-blue.

10.2. Discrete logarithm problem

The secret exchange in the color analogy relied on the fact that mixing two colors is easy, but separating a mixture of two colors is practically impossible. It turns out that there is a mathematical equivalent of this. We call these one-way functions: a function \(f\) such that given \(x\), it is easy to compute \(f(x)\), but given \(y\), it is practically impossible to find a value \(x\) such that \(f(x) = y\).

A one-way function is also sometimes described as the computational equivalent of a process that turns a cow into hamburger: given the cow, you can produce hamburger, but there’s no way to restore the original cow from the hamburger.

There are many functions believed to be one-way functions. The simplest one is exponentiation modulo a prime: \(f(x) = g^x \pmod{p}\), where \(p\) is a large prime and \(g\) is a specially-chosen generator1.

Given \(x\), it is easy to calculate \(f(x)\) (you may recall the repeated squaring algorithm from CS 70). However, given \(f(x) = g^x \pmod{p}\), there is no known efficient algorithm to solve for \(x\). This is known as the discrete logarithm problem, and it is believed to be computationally hard to solve.

Using the hardness of the discrete log problem and the analogy from above, we are now ready to construct the Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol.

10.3. Diffie-Hellman protocol

In high-level terms, the Diffie-Hellman key exchange works like this.

Alice and Bob first establish the public parameters \(p\) and \(g\). Remember that \(p\) is a large prime and \(g\) is a generator in the range \(1<g<p-1\). For instance, Alice could pick \(p\) and \(g\) and then announce it publicly to Bob. Today, \(g\) and \(p\) are often hardcoded or defined in a standard so they don’t need to be chosen each time. These values don’t need to be specific to Alice or Bob in any way, and they’re not secret.

Then, Alice picks a secret value \(a\) at random from the set \(\{0,1,\dots,p-2\}\), and she computes \(A=g^a \bmod p\). At the same time, Bob randomly picks a secret value \(b\) and computes \(B=g^b \bmod p\).

Now Alice announces the value \(A\) (keeping \(a\) secret), and Bob announces \(B\) (keeping \(b\) secret). Alice uses her knowledge of \(B\) and \(a\) to compute

\[S = B^a = (g^b)^a = g^{ba} \pmod p.\]Symmetrically, Bob uses his knowledge of \(A\) and \(b\) to compute

\[S = A^b = (g^a)^b = g^{ab} \pmod p.\]Note that \(g^{ba} = g^{ab} \pmod{p}\), so both Alice and Bob end up with the same result, \(S\).

Finally, Alice and Bob can use \(S\) as a shared key for a symmetric-key cryptosystem (in practice, we would apply some hash function to \(S\) first and use the result as our shared key, for technical reasons).

The amazing thing is that Alice and Bob’s conversation is entirely public, and from this public conversation, they both learn this secret value \(S\)—yet eavesdroppers who hear their entire conversation cannot learn \(S\).

As far as we know, there is no efficient algorithm to deduce \(S=g^{ab} \bmod p\) from the values Eve sees, namely \(A=g^a \bmod p\), \(B=g^b \bmod p\), \(g\), and \(p\). The hardness of this problem is closely related to the discrete log problem discussed above. In particular, the fastest known algorithms for solving this problem take \(2^{cn^{1/3} (\log n)^{2/3}}\) time, if \(p\) is a \(n\)-bit prime. For \(n=2048\), these algorithms are far too slow to allow reasonable attacks.

Here is how this applies to secure communication among computers. In a computer network, each participant could pick a secret value \(x\), compute \(X=g^x \bmod p\), and publish \(X\) for all time. Then any pair of participants who want to hold a conversation could look up each other’s public value and use the Diffie-Hellman scheme to agree on a secret key known only to those two parties. This means that the work of picking \(p\), \(g\), \(x\), and \(X\) can be done in advance, and each time a new pair of parties want to communicate, they each perform only one modular exponentiation. Thus, this can be an efficient way to set up shared keys.

Here is a summary of Diffie-Hellman key exchange:

-

System parameters: a 2048-bit prime \(p\), a value \(g\) in the range \(2\ldots p-2\). Both are arbitrary, fixed, and public.

-

Key agreement protocol: Alice randomly picks \(a\) in the range \(1\ldots p-2\) and sends \(A=g^a \bmod p\) to Bob. Bob randomly picks \(b\) in the range \(1\ldots p-2\) and sends \(B=g^b \bmod p\) to Alice. Alice computes \(K=B^a \bmod p\). Bob computes \(K=A^b \bmod p\). Alice and Bob both end up with the same random secret key \(K\), yet as far as we know no eavesdropper can recover \(K\) in any reasonable amount of time.

10.4. Elliptic-curve Diffie-Hellman

In the section above, we used the discrete log problem to construct a Diffie-Hellman protocol, but we can generalize Diffie-Hellman key exchange to other one-way functions. One commonly used variant of Diffie-Hellman relies on the elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem, which is based on the math around elliptic curves instead of modular arithmetic. Although the underlying number theory is more complicated, elliptic-curve Diffie-Hellman can use smaller keys than modular arithmetic Diffie-Hellman and still provide the same security, so it has many useful applications.

For this class, you don’t need to understand the underlying math that makes elliptic-curve Diffie-Hellman work, but you should know that the idea behind the protocol is the same.

Alice and Bob start with a publicly known point on the elliptic curve \(G\). Alice chooses a secret integer \(a\) and Bob chooses a secret integer \(b\).

Alice computes \(A = a \cdot G\) (this is a point on the curve \(A\), obtained by adding the point \(G\) to itself \(a\) times), and Bob computes \(B = b \cdot G\). Alice sends \(A\) to Bob, and Bob sends \(B\) to Alice.

Alice computes

\[S = a \cdot B = a \cdot b \cdot G\]and Bob computes

\[S = b \cdot A = b \cdot a \cdot G\]Because of the properties of the elliptic curve, Alice and Bob will derive the same point \(S\), so they now have a shared secret. Also, the elliptic-curve Diffie-Hellman problem states that given \(A = a \cdot G\) and \(B = b \cdot G\), there is no known efficient method for Eve to calculate \(S\).

10.5. Difficulty in Bits

It is generally believed that the discrete log problem is hard, but how hard? In practice, it is generally believed that computing the discrete log modulo a 2048b prime, computing the elliptic curve discrete log on a 256b curve, and brute forcing a 128b symmetric key algorithm are all roughly the same difficulty. (Brute-forcing the 128b key is believed to be slightly harder than the other two.)

Thus, if we are using Diffie-Hellman key exchange with other cryptoschemes, we try to relate the difficulty of the schemes so that it is equally difficult for an attacker to break any scheme. For example, 128b AES tends to be used with SHA-256 and either 256b elliptic curves or 2048b primes for Diffie-Hellman. Similarly, for top-secret use, the NSA uses 256b AES, 384b Elliptic Curves, SHA-384, and 3096b Diffie-Hellman and RSA.

10.6. Attacks on Diffie-Hellman

As we’ve seen, Diffie-Hellman is secure against an eavesdropper Eve, who observes the messages sent between Alice and Bob, but does not tamper with them. What if we replace Eve with Mallory, an active adversary (man-in-the-middle) who can tamper with messages?

It turns out the Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol is only secure against a passive adversary and not an active adversary. If Mallory can tamper with the communication between Alice and Bob, she can fool them into thinking that they’ve agreed with a shared key, when they have actually generated two different keys that Mallory knows.

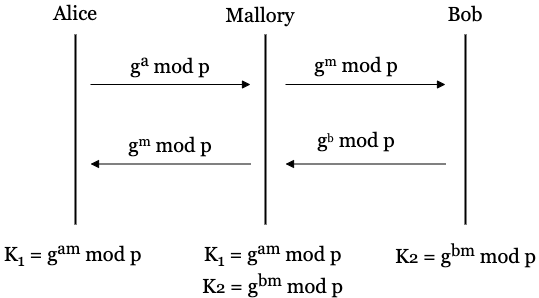

The following figure demonstrates how an active attacker (Mallory) can agree on a key (\(K_1=g^{am} \pmod{p}\)) with Alice and another key (\(K_2=g^{bm} \pmod{p}\)) with Bob in order to man-in-the-middle (MITM) their communications.

When Alice sends \(g^a \pmod{p}\) to Bob, Mallory intercepts the message and replaces it with \(g^m \pmod{p}\), where \(m\) is Mallory’s secret. Bob now receives \(g^m \pmod{p}\) instead of \(g^a \pmod{p}\). Now, when Bob wants to calculate his shared key, he will calculate \(K = A^b \pmod{p}\), where \(A\) is the value he received from Alice. Since he received a tampered value from Mallory, Bob will actually calculate \(K = (g^m)^b = g^{mb} \pmod{p}\).

Likewise, when Bob sends \(g^b \pmod{p}\) to Alice, Mallory intercepts the message and replaces it with \(g^m \pmod{p}\). Alice receives \(g^m \pmod{p}\). To calculate her shared key, she calculates \(K = B^a \pmod{p}\), where \(B\) is the value she received from Bob. Since Alice received a tampered value, she will actually calculate \(K = (g^m)^a = g^{ma} \pmod{p}\).

After the exchange, Alice thinks the shared key is \(g^{ma} \pmod{p}\) and Bob thinks the shared key is \(g^{mb} \pmod{p}\). They no longer have the same shared secret.

Even worse, Mallory knows both of these values too. Mallory intercepted Alice sending \(g^a \pmod{p}\), which means Mallory knows the value of \(g^a \pmod{p}\). She also knows her own chosen secret \(m\). Thus she can calculate \((g^a)^m = g^{am} \pmod{p}\), which is what Alice thinks her shared secret is. Likewise, Mallory intercepted \(g^b \pmod{p}\) from Bob and can calculate \((g^b)^m = g^{bm} \pmod{p}\), which is what Bob thinks his shared secret is.

If Alice and Bob fall victim to this attack, Mallory can now decrypt any messages sent from Alice with Alice’s key \(g^{ma} \pmod{p}\), make any changes to the message, re-encrypt the message with Bob’s key \(g^{mb} \pmod{p}\), and send it to Bob. In other words, Mallory would pretend to Alice that she is Bob, and pretend to Bob that she is Alice. This would not only allow Mallory to eavesdrop on the entire conversation but also make changes to the messages without Alice and Bob ever noticing that they are under attack.

The main reason why the Diffie-Hellman protocol is vulnerable to this attack is that the messages exchanged between Alice and Bob have no integrity or authenticity. To defend against this attack, Alice and Bob will need to additionally use a cryptoscheme that provides integrity and authenticity, such as digital signatures. If the messages sent during the Diffie-Hellman exchange have integrity and authenticity, then Alice and Bob would be able to detect Mallory’s tampering with the messages.

Past Exam Questions

Here we’ve compiled a list of past exam questions that cover Diffie-Hellman key exchange.

- Spring 2024 Final Question 6: Plentiful Playlists

- Summer 2023 Midterm Question 7: Oblivious Transfer

-

You don’t need to worry about how to choose \(g\), just know that it satisfies some special number theory properties. In short, \(g\) must satisfy the following properties: \(1 < g < p-1\), and there exists a \(k\) where \(g^k = a\) for all \(1 \leq a \leq p-1\). ↩