6. Symmetric-Key Encryption

In this section, we will build symmetric-key encryption schemes that guarantee confidentiality. Because we are in the symmetric key setting, in this section we can assume that Alice and Bob share a secret key that is not known to anyone else. Later we will see how Alice and Bob might securely exchange a shared secret key over an insecure communication channel, but for now you can assume that only Alice and Bob know the value of the secret key.

For modern schemes, we are going to assume that all messages are bitstrings, which is a sequence of bits, 0 or 1 (e.g. 1101100101010101). Text, images, and most other forms of communication can usually be converted into bitstrings before encryption, so this is a useful abstraction.

6.1. IND-CPA Security

Recall from the previous chapter that confidentiality was defined to mean that an attacker cannot read our messages. This definition, while intuitive, is quite open-ended. If the attacker can read the first half of our message but not the second half, is that confidential? What if the attacker can deduce that our message starts with the words “Dear Bob?” It might also be the case that the attacker had some partial information about the message \(M\) to begin with. Perhaps she knew that the last bit of \(M\) is a \(0\), or that \(90\%\) of the bits of \(M\) are \(1\)’s, or that \(M\) is one of BUY! or SELL but does not know which.

A more formal, rigorous definition of confidentiality is: the ciphertext \(C\) should give the attacker no additional information about the message \(M\). In other words, the attacker should not learn any new information about \(M\) beyond what they already knew before seeing \(C\) (seeing \(C\) should not give the attacker any new information).

We can further formalize this definition by designing an experiment to test whether the attacker has learned any additional information. Consider the following experiment: Alice has encrypted and sent one of two messages, either \(M_0\) or \(M_1\), and the attacker, Eve, has no idea which was sent. Eve tries to guess which was sent by looking at the ciphertext. If the encryption scheme is confidential, then Eve’s probability of guessing which message was sent should be \(1/2\), which is the same probability as if she had not intercepted the ciphertext at all, and was instead guessing at random.

We can adapt this experiment to different threat models by allowing Eve to perform further actions as an attacker. For example, Eve might be allowed to trick Alice into encrypting some messages of Eve’s choosing. Eve might also be allowed to trick Bob into decrypting some ciphertexts of Eve’s choosing. In this class, we will be focusing on the chosen-plaintext attack model, which means Eve can trick Alice into encrypting some messages, but she cannot trick Alice into decrypting some messages.

In summary, our definition of confidentiality says that even if Eve can trick Alice into encrypting some messages, she still cannot distinguish whether Alice sent \(M_0\) or \(M_1\) in the experiment. This definition is known as indistinguishability under chosen plaintext attack, or IND-CPA. We can use an experiment or game, played between the adversary Eve and the challenger Alice, to formally prove that a given encryption scheme is IND-CPA secure or show that it is not IND-CPA secure.

The IND-CPA game works as follows:

-

The adversary Eve chooses two different messages, \(M_0\) and \(M_1\), and sends both messages to Alice.

-

Alice flips a fair coin. If the coin is heads, she encrypts \(M_0\). If the coin is tails, she encrypts \(M_1\). Formally, Alice chooses a bit \(b \in \{0, 1\}\) uniformly at random, and then encrypts \(M_b\). Alice sends the encrypted message \(Enc(K, M_b)\) back to Eve.

-

Eve is now allowed to ask Alice for encryptions of messages of Eve’s choosing. Eve can send a plaintext message to Alice, and Alice will always send back the encryption of the message with the secret key. Eve is allowed to repeat this as many times as she wants. Intuitively, this step is allowing Eve to perform a chosen-plaintext attack in an attempt to learn something about which message was sent.

-

After Eve is finished asking for encryptions, she must guess whether the encrypted message from step 2 is the encryption of \(M_0\) or \(M_1\).

If Eve can guess which message was sent with probability \(> 1/2\), then Eve has won the game. This means that Eve has learned some information about which message was sent, so the scheme is not IND-CPA secure. On the other hand, if Eve cannot do any better than guess with \(1/2\) probability, then Alice has won the game. Eve has learned nothing about which message was sent, so the scheme is IND-CPA secure.

There are a few important caveats to the IND-CPA game to make it a useful, practical security definition:

The messages \(M_0\) and \(M_1\) must be the same length. In almost all practical cryptosystems, we allow ciphertexts to leak the length of the plaintext. Why? If we want a scheme that doesn’t reveal the length of the plaintext, then we would need every ciphertext to be the same length. If the ciphertext is always \(n\) bits long, then we wouldn’t be able to encrypt any messages longer than \(n\) bits, which makes for a very impractical system. You could make \(n\) very large so that you can encrypt most messages, but this would mean encrypting a one-bit message requires an enormous \(n\)-bit ciphertext. Either way, such a system would be very impractical in real life, so we allow cryptosystems to leak the length of the plaintext.

If we didn’t force \(M_0\) and \(M_1\) to be the same length, then our game would incorrectly mark some IND-CPA secure schemes as insecure. In particular, if a scheme leaks the plaintext length, it can still be considered IND-CPA secure. However, Eve would win the IND-CPA game with this scheme, since she can send a short message and a long message, see if Alice sends back a short or long ciphertext, and distinguish which message was sent. To account for the fact that cryptosystems can leak plaintext length, we use equal-length messages in the IND-CPA game.

Eve is limited to a practical number of encryption requests. In practice, some schemes may be vulnerable to attacks but considered secure anyway, because those attacks are computationally infeasible. For example, Eve could try to brute-force a 128-bit secret key, but this would take \(2^{128}\) computations. If each computation took 1 millisecond, this would take \(10^{28}\) years, far longer than the age of our solar system. These attacks may be theoretically possible, but they are so inefficient that we don’t need to worry about attackers who try them. To account for these computationally infeasible attacks in the IND-CPA game, we limit Eve to a practical number of encryption requests. One commonly-used measure of practicality is polynomially-bounded runtime: any algorithm Eve uses during the game must run in \(O(n^k)\) time, for some constant \(k\).

Eve only wins if she has a non-negligible advantage. Consider a scheme where Eve can correctly which message was sent with probability \(1/2 + 1/2^{128}\). This number is greater than \(1/2\), but Eve’s advantage is \(1/2^{128}\), which is astronomically small. In this case, we say that Eve has negligible advantage–the advantage is so small that Eve cannot use it to mount any practical attacks. For example, the scheme might use a 128-bit key, and Eve can break the scheme if she guesses the key (with probability \(1/2^{128}\)). Although this is theoretically a valid attack, the odds of guessing a 128-bit key are so astronomically small that we don’t need to worry about it. The exact definition of negligible is beyond the scope of this class, but in short, Eve only wins the IND-CPA game if she can guess which message was sent with probability greater than \(1/2 + n\), where \(n\) is some non-negligible probability.

You might have noticed that in step 3, there is nothing preventing Eve from asking Alice for the encryption of \(M_0\) or \(M_1\) again. This is by design: it means any deterministic scheme is not IND-CPA secure, and it forces any IND-CPA secure scheme to be non-deterministic. Informally, a deterministic scheme is one that, given a particular input, will always produce the same output. For example, the Caesar Cipher that was seen in the previous chapter is a deterministic scheme since giving it the same input twice will always produce the same output (i.e. inputting “abcd” will always output “cdef” when we shift by 2). As we’ll see later, deterministic schemes do leak information, so this game will correctly classify them as IND-CPA insecure. In a later section we’ll also see how to win the IND-CPA game against a deterministic scheme.

6.2. XOR review

Symmetric-key encryption often relies on the bitwise XOR (exclusive-or) operation (written as \(\oplus\)), so let’s review the definition of XOR.

\[\begin{aligned} 0 \oplus 0 &= 0 \\ 0 \oplus 1 &= 1 \\ 1 \oplus 0 &= 1 \\ 1 \oplus 1 &= 0 \end{aligned}\]Given this definition, we can derive some useful properties:

\[\begin{aligned} x \oplus 0 &= x & &\text{0 is the identity} \\ x \oplus x &= 0 & &\text{$x$ is its own inverse} \\ x \oplus y &= y \oplus x & &\text{commutative property} \\ (x \oplus y) \oplus z &= x \oplus (y \oplus z) & &\text{associative property} \end{aligned}\]One handy identity that follows from these is: \(x \oplus y \oplus x = y\). In other words, given \((x \oplus y)\), you can retrieve \(y\) by computing \((x \oplus y) \oplus x\), effectively “cancelling out” the \(x\).

We can also perform algebra with the XOR operation:

\[\begin{aligned} y \oplus 1 &= 0 & &\text{goal: solve for y} \\ y \oplus 1 \oplus 1 &= 0 \oplus 1 & &\text{XOR both sides by 1} \\ y &= 1 & &\text{simplify left-hand side using the identity above} \end{aligned}\]6.3. One Time Pad

The first symmetric encryption scheme we’ll look at is the one-time pad (OTP). The one time pad is a simple and idealized encryption scheme that helps illustrate some important concepts, though as we will see shortly, it is impractical for real-world use.

In the one-time pad scheme, Alice and Bob share an \(n\)-bit secret key \(K = k_1 \cdots k_n\) where the bits \(k_1, \ldots k_n\) are picked uniformly at random (they are the outcomes of independent unbiased coin flips, meaning that to pick \(k_1\) a coin is flipped and if it lands on heads, then \(k_1\) is assigned 1, but if it lands on tails, \(k_1\) is assigned 0).

Suppose Alice wishes to send the n-bit message \(M = m_1 \cdots m_n\).

The desired properties of the encryption scheme are:

-

It should scramble up the message, i.e., map it to a ciphertext \(C = c_1 \cdots c_n\).

-

Given knowledge of the secret key \(K\), it should be easy to recover \(M\) from \(C\).

-

Eve, who does not know \(K\), should get no information about \(M\).

Encryption in the one-time pad is very simple: \(c_j = m_j \oplus k_j\). In words, you perform a bitwise XOR of the message and the key. The \(j\)th bit of the ciphertext is the \(j\)th bit of the message, XOR with the \(j\)th bit of the key.

We can derive the decryption algorithm by doing some algebra on the encryption equation:

\[\begin{aligned} c_j &= m_j \oplus k_j & &\text{encryption equation, solve for } m_j \\ c_j \oplus k_j &= m_j \oplus k_j \oplus k_j & &\text{XOR both sides by } k_j \\ c_j \oplus k_j &= m_j & &\text{simplify right-hand side using the handy identity from above} \end{aligned}\]In words, given ciphertext \(C\) and key \(K\), the \(j\)th bit of the plaintext is the \(j\)th bit of the ciphertext, XOR with the \(j\)th bit of the key.

To sum up, the one-time pad is described by specifying three procedures:

-

Key generation: Alice and Bob pick a shared random key \(K\).

-

Encryption algorithm: \(C = M \oplus K\).

-

Decryption algorithm: \(M = C \oplus K\).

One-time pad is information-theoretically secure, in the sense that a ciphertext leaks precisely zero information about its plaintext. For a fixed choice of plaintext \(M\), every possible value of the ciphertext \(C\) can be achieved by an appropriate and unique choice of the shared key \(K\): namely \(K = M \oplus C\). Since each such key value \(K\) is equally likely, it follows that \(C\) is also equally likely to be any \(n\)-bit string. Thus the eavesdropper sees a uniformly random \(n\) bit string no matter what the plaintext message was, presuming the key is randomly chosen and used only once.

The one time pad has a major drawback. As its name suggests, the shared key cannot be reused to transmit another message \(M'\). If the key \(K\) is reused to encrypt two messages \(M\) and \(M'\), then Eve can take the XOR of the two ciphertexts \(C = M \oplus K\) and \(C' = M' \oplus K\) to obtain \(C \oplus C' = M \oplus M'\). This gives partial information about the two messages. In particular, if Eve happens to learn \(M\), then she can deduce the other message \(M'\). In other words, given \(M \oplus M'\) and \(M\), she can calculate \(M' = (M \oplus M') \oplus M\). Actually, in this case, she can reconstruct the key \(K\), too. Question: How?1

In practice, even if Eve does not know \(M\) or \(M'\), often there is enough redundancy in messages that merely knowing \(M \oplus M'\) is enough to recover most of \(M\) and \(M'\). For instance, the US exploited this weakness to read some World War II era Soviet communications encrypted with the one-time pad, when US cryptanalysts discovered that Soviet officials in charge of generating random keys for the one-time pad got lazy and started re-using old keys. The VENONA project, although initiated just shortly after World War II, remained secret until the early 1980s.

We can see that the one-time pad with key reuse is insecure because Eve has learned something about the original messages (namely, the XOR of the two original messages). We can also formally prove that the one-time pad with key reuse is not IND-CPA secure by showing a strategy for the adversary Eve to correctly guess which message was encrypted, with probability greater than \(1/2\).

Eve sends two messages, \(M_0\) and \(M_1\) to the challenger. The challenger randomly chooses one message to encrypt and sends it back to Eve. At this point, Eve knows she has received either \(M_0 \oplus K\) or \(M_1 \oplus K\), depending on which message was encrypted. Eve is now allowed to ask for the encryption of arbitrary messages, so she queries the challenger for the encryption of \(M_0\). The challenger is using the same key for every message, so Eve will receive \(M_0 \oplus K\). Eve can now compare this value to the encryption she is trying to guess: if the value matches, then Eve knows that the challenger encrypted \(M_0\) and sent \(M_0 \oplus K\). If the value doesn’t match, then Eve knows that the challenger encrypted \(M_1\) and sent \(M_1 \oplus K\). Thus Eve can guess which message the challenger encrypted with 100% probability! This is greater than \(1/2\) probability, so Eve has won the IND-CPA game, and we have proven that the one-time pad scheme with key reuse is insecure.

Consequently, the one-time pad is not secure if the key is used to encrypt more than one message. This makes it impractical for almost all real-world situations–if Alice and Bob want to encrypt an \(n\)-bit message with a one-time pad, they will first need to securely send each other a new, previously unused \(n\)-bit key. But if they’ve found a method to securely exchange an \(n\)-bit key, they could have just used that same method to exchange the \(n\)-bit message!2

6.4. Block Ciphers

As we’ve just seen, generating new keys for every encryption is difficult and expensive. Instead, in most symmetric encryption schemes, Alice and Bob share a secret key and use this single key to repeatedly encrypt and decrypt messages. The block cipher is a fundamental building block in implementing such a symmetric encryption scheme.

Intuitively, a block cipher transforms a fixed-length, \(n\)-bit input into a fixed-length \(n\)-bit output. The block cipher has \(2^k\) different settings for scrambling, so it also takes in a \(k\)-bit key as input to determine which scrambling setting should be used. Each key corresponds to a different scrambling setting. The idea is that an attacker who doesn’t know the secret key won’t know what mode of scrambling is being used, and thus won’t be able to decrypt messages encrypted with the block cipher.

A block cipher has two operations: encryption takes in an \(n\)-bit plaintext and a \(k\)-bit key as input and outputs an \(n\)-bit ciphertext. Decryption takes in an \(n\)-bit ciphertext and a \(k\)-bit key as input and outputs an \(n\)-bit plaintext. Question: why does the decryption require the key as input?3

Given a fixed scrambling setting (key), the block cipher encryption must map each of the \(2^n\) possible plaintext inputs to a different ciphertext output. In other words, given a specific key, the block cipher encryption must be able to map every possible input to a unique output. If the block cipher mapped two plaintext inputs to the same ciphertext output, there would be no way to decrypt that ciphertext back into plaintext, since that ciphertext could correspond to multiple different plaintexts. This means that the block cipher must also be deterministic. Given the same input and key, the block cipher should always give the same output.

In mathematical notation, the block cipher can be described as follows. There is an encryption function \(E: \{0,1\}^k \times \{0,1\}^n \rightarrow \{0,1\}^n\). This notation means we are mapping a \(k\)-bit input (the key) and an \(n\)-bit input (the plaintext message) to an \(n\)-bit output (the ciphertext). Once we fix the key \(K\), we get a function mapping \(n\) bits to \(n\) bits: \(E_K:\{0,1\}^n \rightarrow \{0,1\}^n\) defined by \(E_K(M) = E(K, M)\). \(E_K\) is required to be a permutation on the \(n\)-bit strings, in other words, it must be an invertible (bijective) function. The inverse mapping of this permutation is the decryption algorithm \(D_K\). In other words, decryption is the reverse of encryption: \(D_K(E_K(M)) = M\).

The block cipher as defined above is a category of functions, meaning that there are many different implementations of a block cipher. Today, the most commonly used block cipher implementation is called Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). It was designed in 1998 by Joan Daemen and Vincent Rijmen, two researchers from Belgium, in response to a competition organized by NIST.4

AES uses a block length of \(n=128\) bits and a key length of \(k=128\) bits. It can also support \(k=192\) or \(k=256\) bit keys, but we will assume 128-bit keys in this class. It was designed to be extremely fast in both hardware and software.

6.5. Block Cipher Security

Block ciphers, including AES, are not IND-CPA secure on their own because they are deterministic. In other words, encrypting the same message twice with the same key produces the same output twice. The strategy that an adversary, Eve, uses to break the security of AES is exactly the same as the strategy from the one-time pad with key reuse. Eve sends \(M_0\) and \(M_1\) to the challenger and receives either \(E(K, M_0)\) or \(E(K, M_1)\). She then queries the challenger for the encryption of \(M_0\) and receives \(E(K, M_0)\). If the two encryptions she receives from the challenger are the same, then Eve knows the challenger encrypted \(M_0\) and sent \(E(K, M_0)\). If the two encryptions are different, then Eve knows the challenger encrypted \(M_1\) and sent \(E(K, M_1)\). Thus Eve can win the IND-CPA game with probability 100% \(> 1/2\), and the block cipher is not IND-CPA secure.

Although block ciphers are not IND-CPA secure, they have a desirable security property that will help us build IND-CPA secure symmetric encryption schemes: namely, a block cipher is computationally indistinguishable from a random permutation. In other words, for a fixed key \(K\), \(E_K\) “behaves like” a random permutation on the \(n\)-bit strings.

A random permutation is a function that maps each \(n\)-bit input to exactly one random \(n\)-bit output. One way to generate a random permutation is to write out all \(2^n\) possible inputs in one column and all \(2^n\) possible outputs in another column, and then draw \(2^n\) random lines connecting each input to each output. Once generated, the function itself is not random: given the same input twice, the function gives the same output twice. However, the choice of which output is given is randomly determined when the function is created.

Formally, we perform the following experiment to show that a block cipher is indistinguishable from a random permutation. The adversary, Eve, is given a box which contains either (I) the encryption function \(E_K\) with a randomly chosen key \(K\), or (II) a permutation \(\pi\) on \(n\) bits chosen uniformly at random when the box was created (in other words, map each \(n\)-bit input to a different random \(n\)-bit output). The type of box given to Eve is randomly selected, but we don’t tell Eve which type of box she has been given. We also don’t tell Eve the value of the key \(K\).

Eve is now allowed to play with the box as follows: Eve can supply an input \(x\) to the box and receive a corresponding output \(y\) from the box (namely, \(y=E_K(x)\) for a type-I box, or \(y=\pi(x)\) for a type-II box). After playing with the box, Eve must guess whether the box is type I or type II. If the block cipher is truly indistinguishable from random, then Eve cannot guess which type of box she received with probability greater than \(1/2\).

AES is not truly indistinguishable from random, but it is believed to be computationally indistinguishable from random. Intuitively, this means that given a practical amount of computation power (e.g. polynomially-bounded runtime), Eve cannot guess which type of box she received with probability greater than \(1/2\). Another way to think of computational indistinguishability is: Eve can guess which type of box she received with probability \(1/2\), plus some negligible amount (e.g. \(1/2^{128}\)). With infinite computational time and power, Eve could leverage this tiny \(1/2^{128}\) advantage to guess which box she received, but with only a practical amount of computation power, this advantage is useless for Eve.

The computational indistinguishability property of AES gives us a strong security guarantee: given a single ciphertext \(C = E_K(M)\), an attacker without the key cannot learn anything about the original message \(M\). If the attacker could learn something about \(M\), then AES would no longer be computationally indistinguishable: in the experiment from before, Eve could feed \(M\) into the box and see if given only the output from the box, she can learn something about \(M\). If Eve learns something about \(M\), then she knows the output came from a block cipher. If Eve learns nothing about \(M\), then she knows the output came from a random permutation. However, since we believe that AES is computationally indistinguishable from random, we can say that an attacker who receives a ciphertext learns nothing about the original message.

There is no proof that AES is computationally indistinguishable from random, but it is believed to be computationally indistinguishable. After all these years, the best known attack is still exhaustive key search, where the attacker systematically tries decrypting some ciphertext using every possible key to see which one gives intelligible plaintext. Given infinite computational time and power, exhaustive key search can break AES, which is why it is not truly indistinguishable from random. However, with a 128-bit key, exhaustive key search requires \(2^{128}\) computations in the worst case (\(2^{127}\) on average). This is a large enough number that even the fastest current supercomputers couldn’t possibly mount an exhaustive key search attack against AES within the lifetime of our Solar system.

Thus AES behaves very differently than the one-time pad. Even given a very large number of plaintext/ciphertext pairs, there appears to be no effective way to decrypt any new ciphertexts. We can leverage this property to build symmetric-key encryption schemes where there is no effective way to decrypt any ciphertext, even if it’s the encryption of a message we’ve seen before.

6.6. Block Cipher Modes of Operation

There are two main reasons AES by itself cannot be a practical IND-CPA secure encryption scheme. The first is that we’d like to encrypt arbitrarily long messages, but the block cipher only takes fixed-length inputs. The other is that if the same message is sent twice, the ciphertext in the two transmissions is the same with AES (i.e. it is deterministic). To fix these problems, the encryption algorithm can either be randomized or stateful—it either flips coins during its execution, or its operation depends upon some state information. The decryption algorithm, however, is neither randomized nor stateful.

There are several standard ways (or modes of operation) of building an encryption algorithm, using a block cipher:

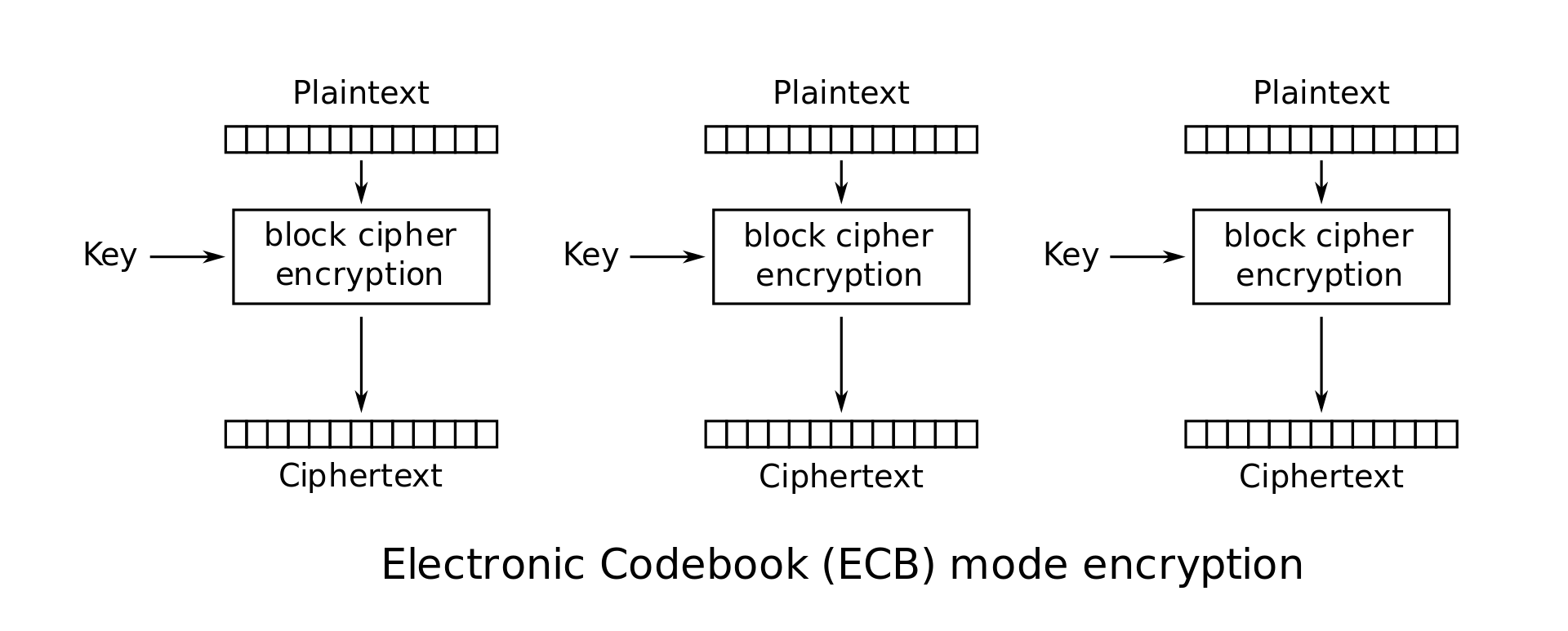

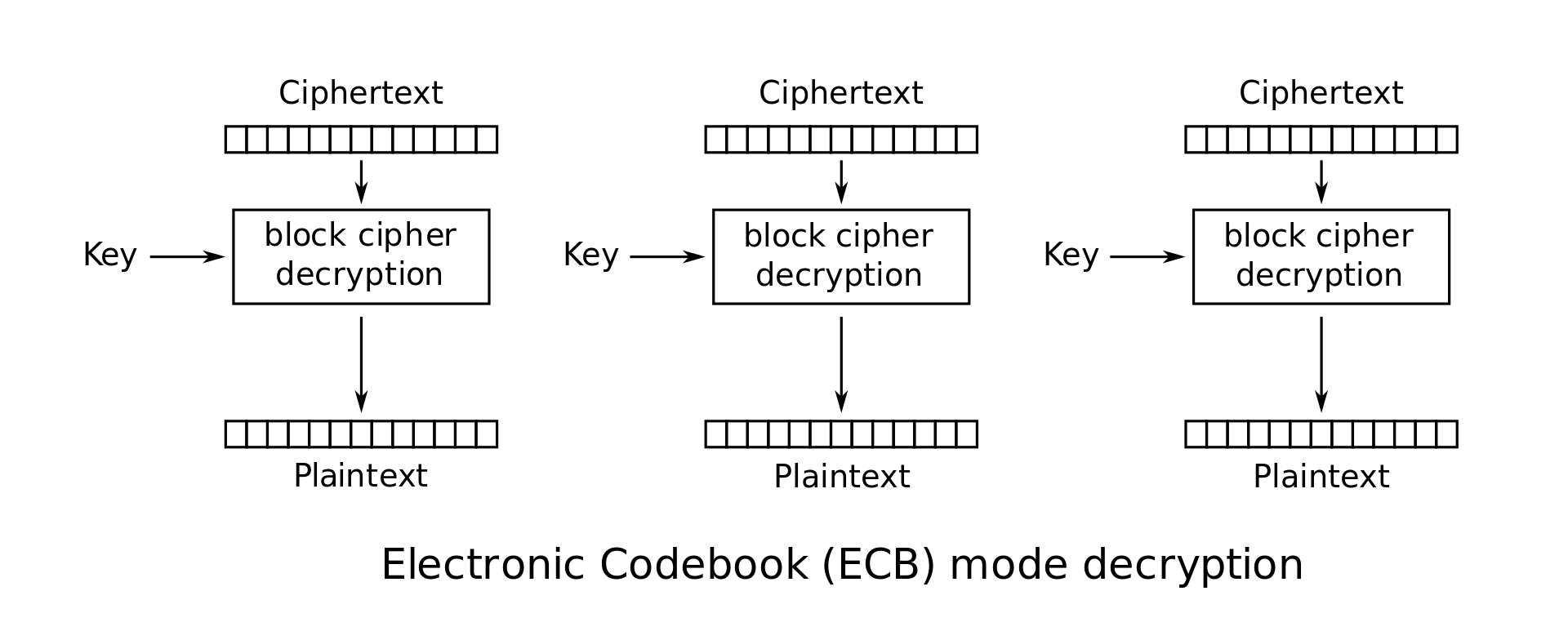

ECB Mode (Electronic Code Book): In this mode the plaintext \(M\) is simply broken into \(n\)-bit blocks \(M_1 \cdots M_l\), and each block is encoded using the block cipher: \(C_i = E_K(M_i)\). The ciphertext is just a concatenation of these individual blocks: \(C = C_1 \cdot C_2 \cdots C_l\). This scheme is flawed. Any redundancy in the blocks will show through and allow the eavesdropper to deduce information about the plaintext. For instance, if \(M_i=M_j\), then we will have \(C_i=C_j\), which is visible to the eavesdropper; so ECB mode leaks information about the plaintext.

-

ECB mode encryption: \(C_i = E_K(M_i)\)

-

ECB mode decryption: \(M_i = D_K(C_i)\)

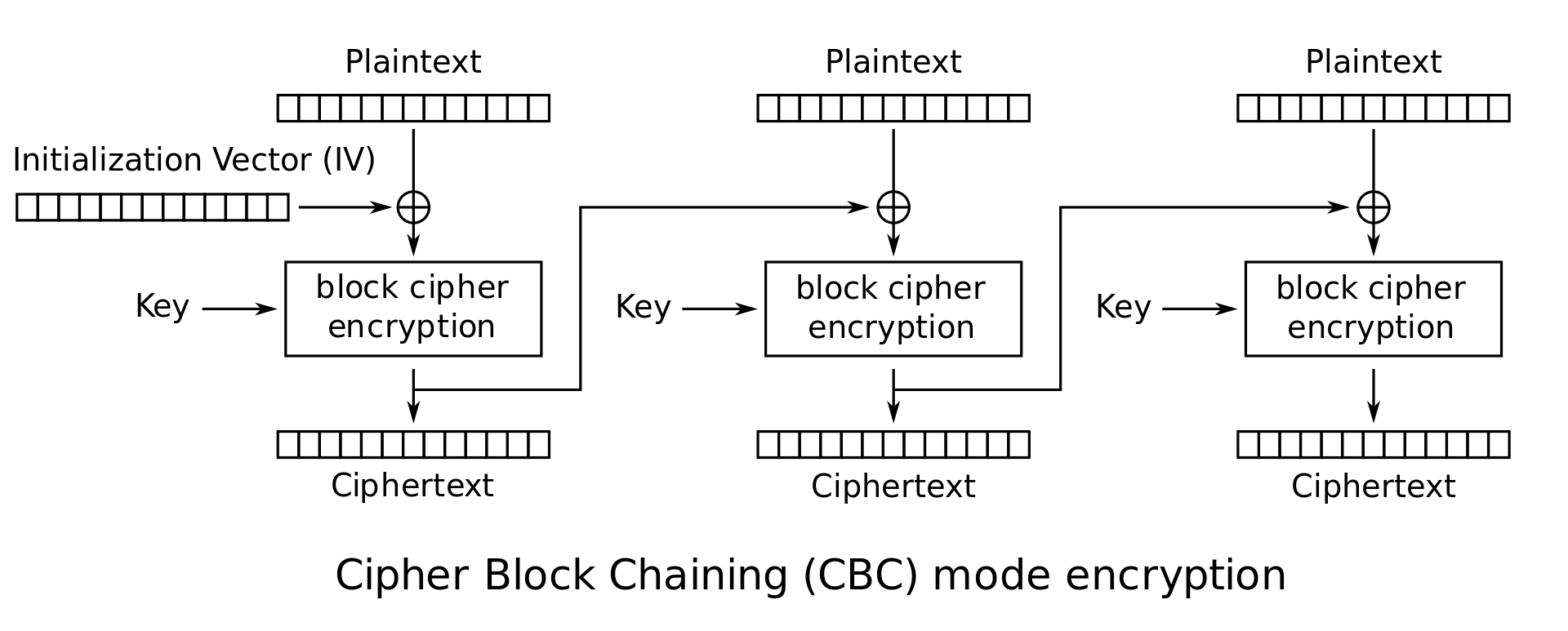

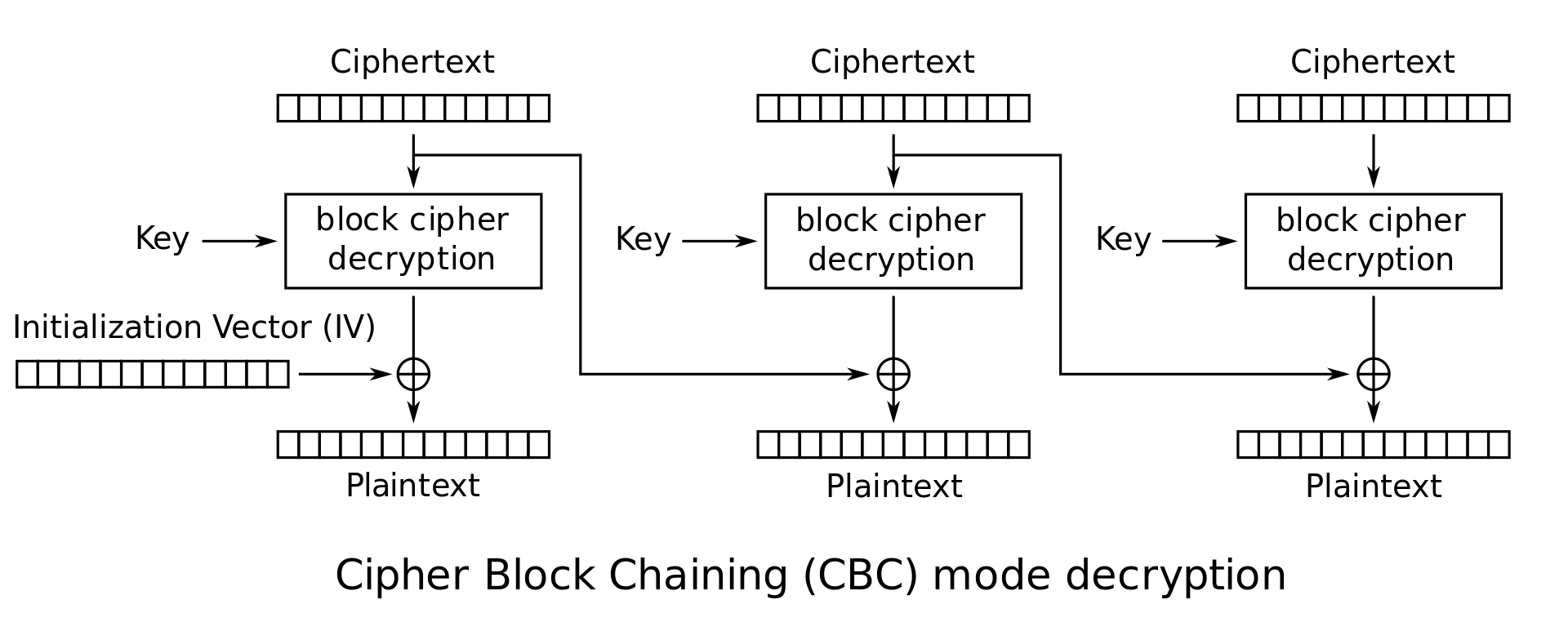

CBC Mode (Cipher Block Chaining): This is a popular mode for commercial applications. For each message the sender picks a random \(n\)-bit string, called the initial vector or IV. Define \(C_0 = IV\). The \(i^\textrm{th}\) ciphertext block is given by \(C_i = E_K(C_{i-1} \oplus M_i)\). The ciphertext is the concatenation of the initial vector and these individual blocks: \(C = IV \cdot C_1 \cdot C_2 \cdots C_l\). CBC mode has been proven to provide strong security guarantees on the privacy of the plaintext message (assuming the underlying block cipher is secure).

-

CBC mode encryption: \(\begin{cases} C_0 = IV \\ C_i = E_K(P_i \oplus C_{i-1}) \end{cases}\)

-

CBC mode decryption: \(P_i = D_K(C_i) \oplus C_{i-1}\)

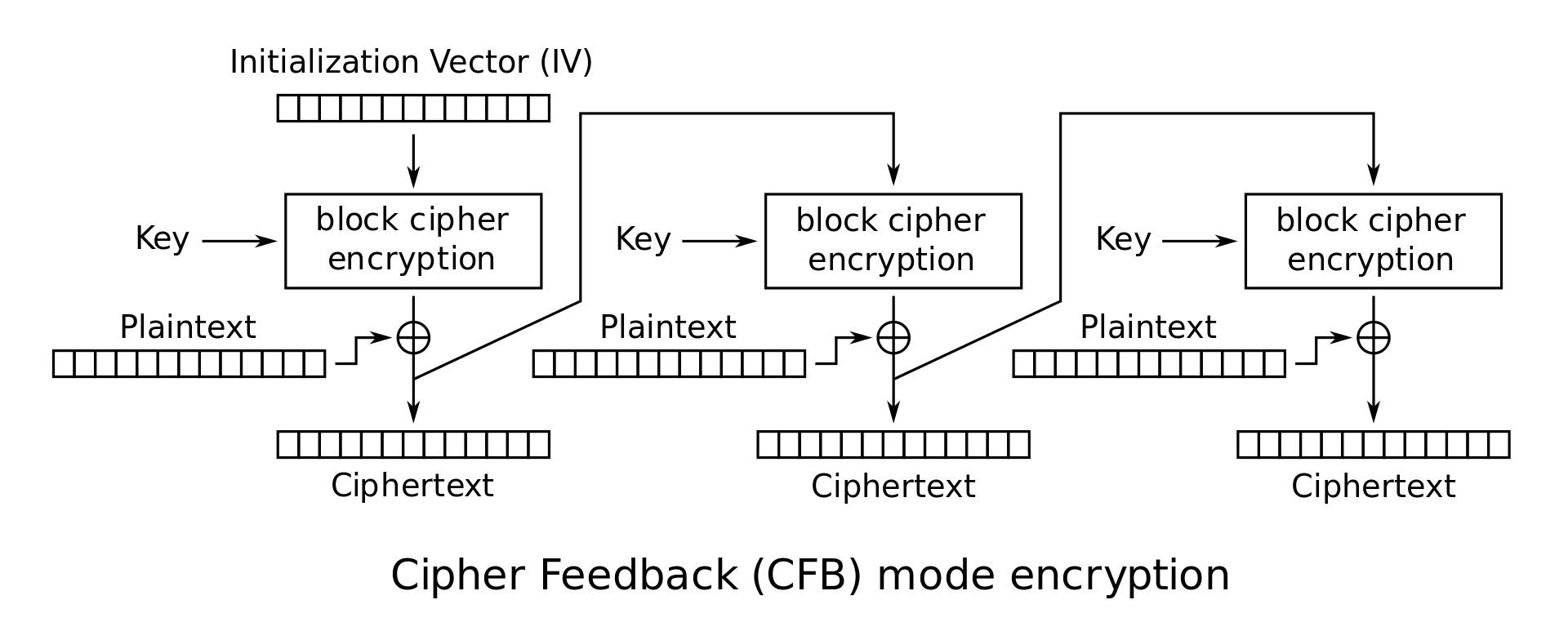

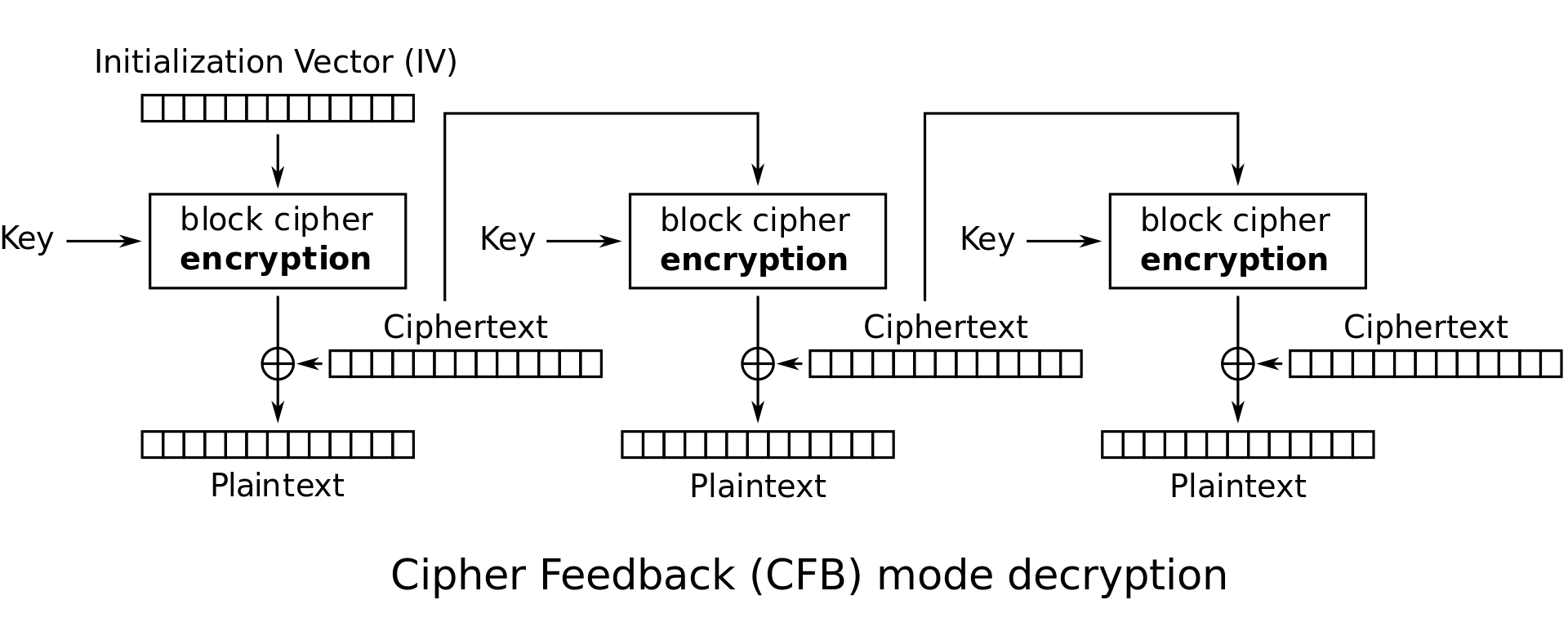

CFB Mode (Ciphertext Feedback Mode): This is another popular mode with properties very similar to CBC mode. Again, \(C_0\) is the IV. The \(i^\textrm{th}\) ciphertext block is given by \(C_i = E_K(C_{i-1}) \oplus M_i\).

-

CFB mode encryption:

\[\begin{cases} C_0 = IV \\ C_i = E_K(C_{i-1}) \oplus P_i \end{cases}\] -

CFB mode decryption: \(P_i = E_K(C_{i-1}) \oplus C_i\)

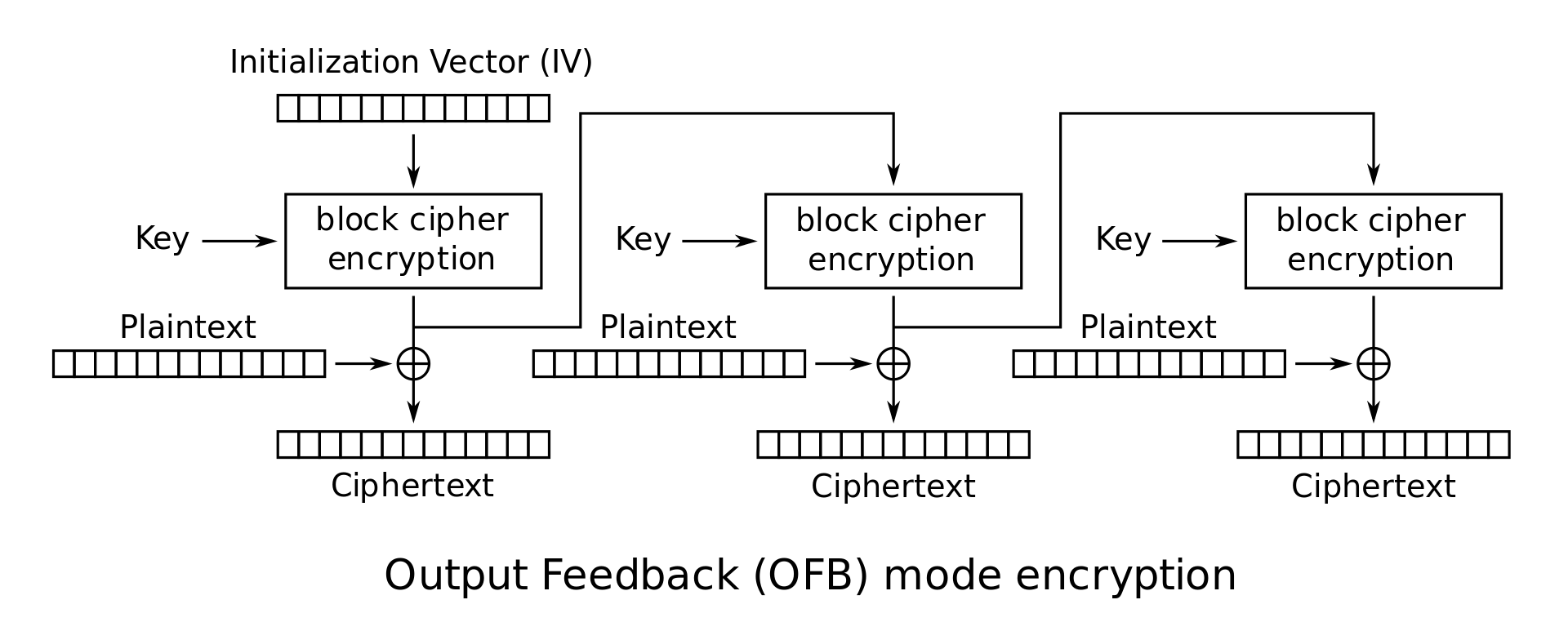

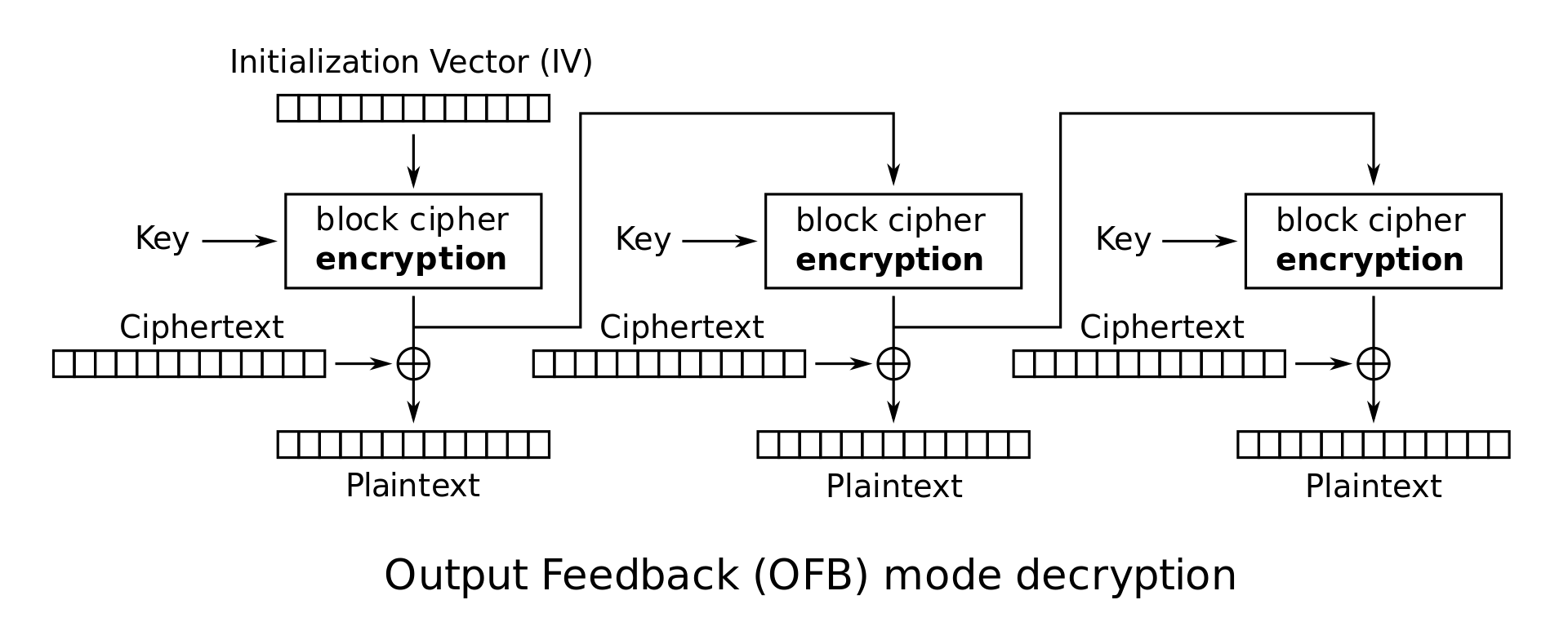

OFB Mode (Output Feedback Mode): In this mode, the initial vector IV is repeatedly encrypted to obtain a set of values \(Z_i\) as follows: \(Z_0 = IV\) and \(Z_i = E_K(Z_{i-1})\). These values \(Z_i\) are now used as though they were the key for a one-time pad, so that \(C_i = Z_i \oplus M_i\). The ciphertext is the concatenation of the initial vector and these individual blocks: \(C = IV \cdot C_1 \cdot C_2 \cdots C_l\). In OFB mode, it is very easy to tamper with ciphertexts. For instance, suppose that the adversary happens to know that the \(j^\textrm{th}\) block of the message, \(M_j\), specifies the amount of money being transferred to his account from the bank, and suppose he also knows that \(M_j = 100\). Since he knows both \(M_j\) and \(C_j\), he can determine \(Z_j\). He can then substitute any \(n\)-bit block in place of \(M_j\) and get a new ciphertext \(C'_j\) where the \(100\) is replaced by any amount of his choice. This kind of tampering is also possible with other modes of operation as well (so don’t be fooled into thinking that CBC mode is safe from tampering); it’s just easier to illustrate on OFB mode.

-

OFB mode encryption:

\[\begin{cases} Z_0 = IV \\ Z_i = E_K(Z_{i-1}) \\ C_i = M_i \oplus Z_i \end{cases}\] -

OFB mode decryption: \(P_i = C_i \oplus Z_i\)

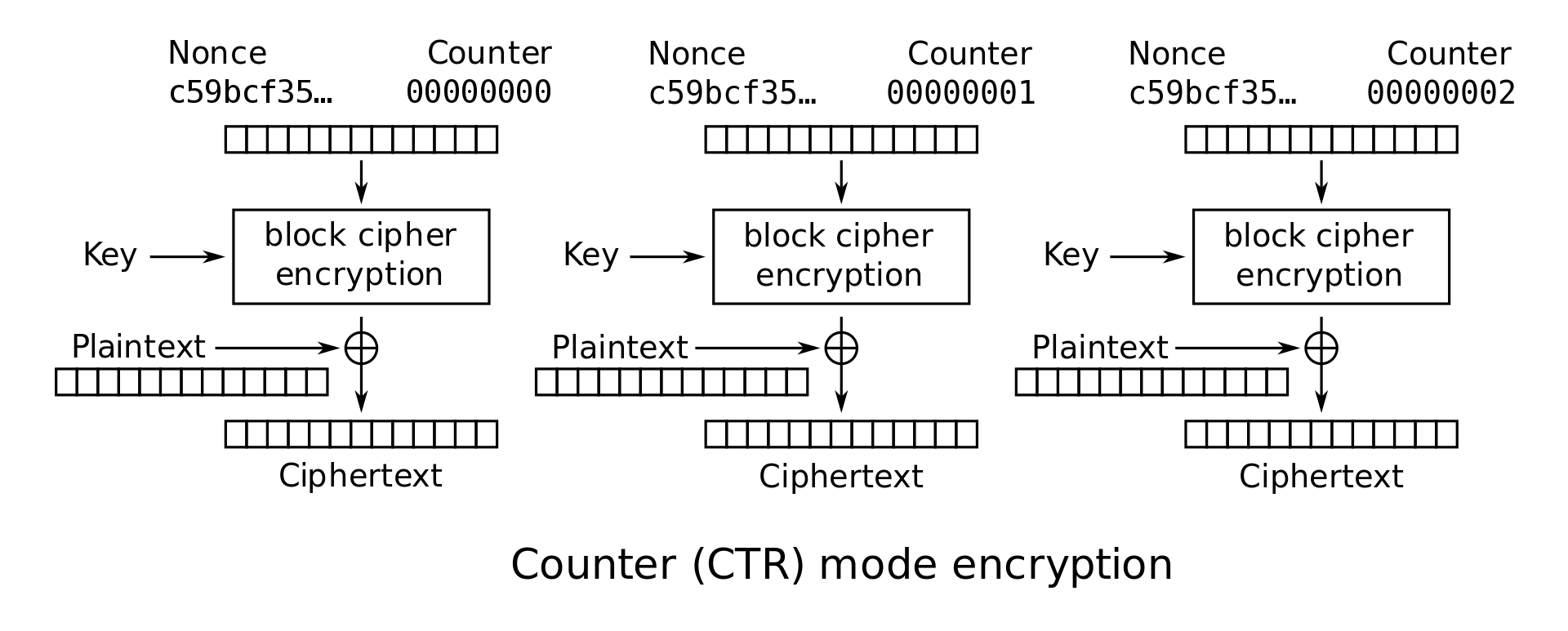

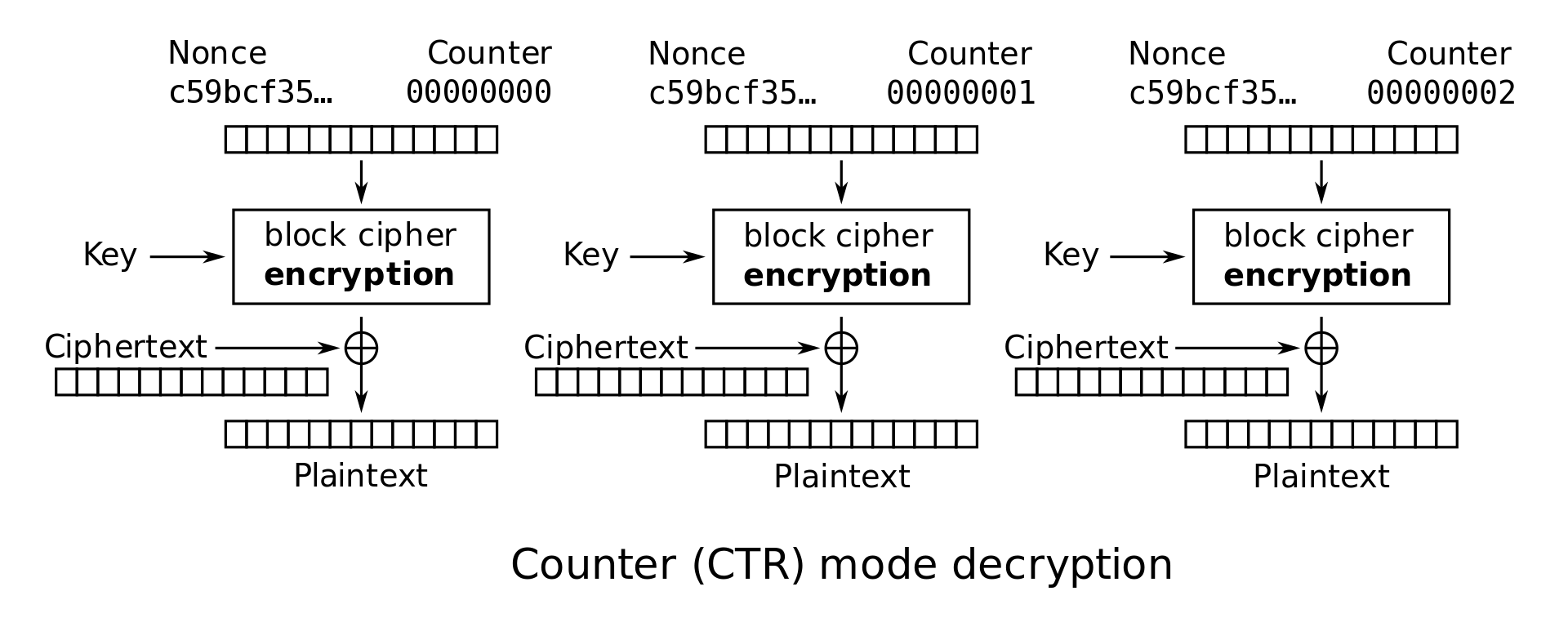

Counter (CTR) Mode: In CTR mode, a counter is initialized to IV and repeatedly incremented and encrypted to obtain a sequence that can now be used as though they were the keys for a one-time pad: namely, \(Z_i = E_K(IV \| i)\) and \(C_i = Z_i \oplus M_i\). In CTR mode, the IV is sometimes renamed the nonce. This is just a terminology difference–nonce and IV can be used interchangeably for the purposes of this class.

Note that in CTR and OFB modes, the decryption algorithm uses the block cipher encryption function instead of the decryption function. Intuitively, this is because Alice used the encryption function to generate a one-time pad, so Bob should also use the encryption function to generate the same pad. The plaintext is never passed through the block cipher encryption, so the block cipher decryption is never used.

-

CTR mode encryption: \(C_i = E_K(IV \| i) \oplus M_i\)

-

CTR mode decryption: \(M_i = E_K(IV \| i) \oplus C_i\)

For the rest of these notes, we will focus on analyzing CBC and CTR modes. As an exercise, you can try performing similar analysis on the other modes as well.

6.7. Parallelization

In some modes, successive blocks must be encrypted or decrypted sequentially. In other words, to encrypt the \(i\)th block of plaintext, you first need to encrypt the \(i-1\)th block of plaintext and see the \(i-1\)th block of ciphertext output. For high-speed applications, it is often useful to parallelize encryption and decryption.

Of the schemes described above, which ones have parallelizable encryption? Which ones have parallelizable decryption?

CBC mode encryption cannot be parallelized. By examining the encryption equation \(C_i = E_K(P_i \oplus C_{i-1})\), we can see that to calculate \(C_i\), we first need to know the value of \(C_{i-1}\). In other words, we have to encrypt the \(i-1\)th block first before we can encrypt the \(i\)th block.

CBC mode decryption can be parallelized. Again, we examine the decryption equation \(P_i = D_K(C_i) \oplus C_{i-1}\). To calculate \(P_i\), we need \(C_i\) and \(C_{i-1}\). Neither of these values need to be calculated–when we’re decrypting, we already have all of the ciphertext blocks. Thus we can compute all the \(P_i\) in parallel.

CTR mode encryption and decryption can both be parallelized. To see this, we can examine the encryption and decryption diagrams. Note that each block cipher only takes the nonce and counter as input, and there is no reliance on any previous ciphertext or plaintext.

6.8. Padding

We have already reasoned that block ciphers let us encrypt messages that are longer than one block long. What happens if we want to send a message that is not a multiple of the block size? It turns out the answer depends on which mode is being used. For this section, assume that the block size is 128 bits, or 16 bytes (16 characters).

In CBC mode, if the plaintext length isn’t a multiple of 128 bits, then the last block of plaintext will be slightly shorter than 128 bits. Then the XOR between the 128-bit previous ciphertext and the less-than-128-bit last block of plaintext would be undefined–bitwise XOR only works if the two inputs being XORed are the same length.

Suppose the last block of plaintext is only 100 bits. What if we just XOR the first 100 bits of the previous ciphertext with the 100 bits of plaintext, and ignore the last 28 bits of the previous ciphertext? Now we have a 100-bit input to the block cipher, which only takes 128-bit inputs. This input is undefined for the block cipher.

The solution to this problem is to add padding to the plaintext until it is a multiple of 128 bits.

If we add padding to make the plaintext a multiple of 128 bits, we will need to be able to remove the padding later to correctly recover the original message. Some forms of padding can create ambiguity: for example, consider a padding scheme where we pad a message with all 1s. What happens if we need to pad a message 0000000010111? We would add 1s until it’s a multiple of the block size, e.g. 0000000010111111. When we try to depad the message, we run into some ambiguity. How many 1s do we remove from the end of the message? It’s unclear.

One correct padding scheme is PKCS#75 padding. In this scheme, we pad the message by the number of padding bytes used. For example, the message above would be padded as 0000000010111333, because 3 bytes of padding were needed. To remove the padding, we note that the message ends in a 3, so 3 bytes of padding were used, so we can unambiguously remove the last 3 bytes of padding. Note that if the message is already a multiple of a block size, an entire new block is appended. This way, there is always one unique padding pattern at the end of the message.

Not all modes need padded plaintext input. For example, let’s look at CTR mode next. Again, suppose we only have 100 bits in your last block of plaintext. This time, we can actually XOR the 100 bits of plaintext with the first 100 bits of block cipher output, and ignore the last 28 bits of block cipher output. Why? Because the result of the XOR never has to be passed into a block cipher again, so we don’t care if it’s slightly shorter than 128 bits. The last ciphertext block will just end up being 100 bits instead of 128 bits, and that’s okay because it’s never used as an input to a block cipher.

How does decryption work? From our encryption step, the last ciphertext block is only 100 bits instead of 128 bits. Then to retrieve the last 100 bits of plaintext, all we have to do is XOR the 100 bits of ciphertext with the first 100 bits of the block cipher output and ignore the last 28 bits of block cipher output.

Recall that CTR mode can be thought of as generating a one-time pad through block ciphers. If the pad is too long, you can just throw away the last few bits of the pad in both the encryption and decryption steps.

6.9. Reusing IVs is insecure

Remember that ECB mode is not IND-CPA secure because it is deterministic. Encrypting the same plaintext twice always results in the same output, and this causes information leakage. All the other modes introduce a random initialization vector (IV) that is different on every encryption in order to ensure that encrypting the same plaintext twice with the same key results in different output.

This also means that when using secure block cipher modes, it is important to always choose a different, random, unpredictable IV for each new encryption. If the same IV is reused, the scheme becomes deterministic, and information is potentially leaked. The severity of information leakage depends on what messages are being encrypted and which mode is being used.

For example, in CTR mode, reusing the IV (nonce) is equivalent to reusing the one-time pad. An attacker who sees two different messages encrypted with the same IV will know the bitwise XOR of the two messages. However, in CBC mode, reusing the IV on two different messages only reveals if two messages start with the same blocks, up until the first difference.

Different modes have different tradeoffs between usability and security. Although proper use of CBC and CTR mode are both IND-CPA, insecure use of either mode (e.g. reusing the IV) breaks IND-CPA security, and the severity of information leakage is different in the two modes. In CBC mode, the information leakage is contained, but in CTR mode, the leakage is catastrophic (equivalent to reusing a one-time pad). On the other hand, CTR mode can be parallelized, but CBC can not, which is why many high performance systems use CTR mode or CTR-mode based encryption schemes.

Past Exam Questions

Here we’ve compiled a list of past exam questions that cover symmetric cryptography.

- Spring 2024 Final Question 5: AES-ROVW

- Spring 2024 Midterm Question 5: Challenging Constructions

- Fall 2023 Final Question 5: Meet Me in the Middle

- Fall 2023 Midterm Question 5: Not Quite by DESign

- Summer 2023 Final Question 5: Ciphertext Thief

- Summer 2023 Midterm Question 5: All or Nothing Security

- Spring 2023 Final Question 5: EvanBlock Cipher

- Spring 2023 Midterm Question 3: IND-CPA and Block Ciphers: evanbotevanbotevanbotevan…

-

Answer: Given \(M\) and \(C = M \oplus K\), Eve can calculate \(K = M \oplus C\). ↩

-

This is why the only primary users of one-time-pads are spies in the field. Before the spy leaves, they obtain a large amount of key material. Unlike the other encryption systems we’ll see in these notes, a one-time pad can be processed entirely with pencil and paper. The spy then broadcasts messages encrypted with the one-time pad to send back to their home base. To obfuscate the spy’s communication, there are also “numbers stations” that continually broadcast meaningless sequences of random numbers. Since the one-time pad is IND-CPA secure, an adversary can’t distinguish between the random number broadcasts and the messages encoded with a one time pad. ↩

-

Answer: The key is needed to determine which scrambling setting was used to generate the ciphertext. If decryption didn’t require a key, any attacker would be able to decrypt encrypted messages! ↩

-

Fun fact: Professor David Wagner, who sometimes teaches this class, was part of the team that came up with a block cipher called TwoFish, which was one of the finalists in the NIST competition. ↩

-

PKCS stands for Public Key Cryptography Standards. ↩