2. x86 Assembly and Call Stack

We provide an overview of x86 assembly, which is a little different from the RISC-V assembly taught in CS 61C.

2.1. Number representation

At the lowest level, computers store memory as individual bits, where each bit is either 0 or 1. There are several units of measurement that we use for collections of bits:

- 1 byte = 8 bits

- 1 word = 32 bits (on 32-bit architectures)

For example, the string 1000100010001000 has 16 bits, or 2 bytes.

A “word” is the size of a pointer, which depends on your CPU architecture. For ease of instruction, this class uses 32-bit architectures unless otherwise stated. Be aware that many modern machines have moved on to 64-bit architectures.

Sometimes we use hexadecimal as a shorthand for writing out long strings of bits. In hexadecimal shorthand, each hexadecimal digit represents 4 bits. The chart below shows conversions between binary and hexadecimal.

| Binary | Hexadecimal | Binary | Hexadecimal |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0000 | 0 | 1000 | 8 |

| 0001 | 1 | 1001 | 9 |

| 0010 | 2 | 1010 | A |

| 0011 | 3 | 1011 | B |

| 0100 | 4 | 1100 | C |

| 0101 | 5 | 1101 | D |

| 0110 | 6 | 1110 | E |

| 0111 | 7 | 1111 | F |

To distinguish between binary and hexadecimal strings, we put 0b before binary strings and 0x before hexadecimal strings.

Sanity check: Convert the binary string 0b1100000101100001 into hexadecimal.1

2.2. Compiler, Assembler, Linker, Loader

There are four main steps to running a C program:

- The compiler translates your C code into assembly instructions. CS 61C introduces the RISC-V instruction set. In 161, we use x86, which is more common than RISC-V in servers and desktops.

- The assembler translates the assembly instructions from the compiler into machine code (raw bits). You might remember using the RISC-V green sheet to translate assembly instructions into raw bits in CS 61C. This is what the assembler does.

- The linker resolves dependencies on external libraries. After the linker is finished linking external libraries, it outputs a binary executable of the program that you can run. You can mostly ignore the linker for the purposes of this class.

- When the user runs the executable, the loader sets up an address space in memory and runs the machine code instructions in the executable.

2.3. C memory layout

At runtime, the operating system gives the program an address space to store any state necessary for program execution. You can think of the address space as a large, contiguous chunk of memory. Each byte of memory has a unique address.

The size of the address space depends on your operating system and CPU architecture. In a 32-bit system, memory addresses are 32 bits long, which means the address space has \(2^{32}\) bytes of memory. In a 64-bit system, memory addresses are 64 bits long. (Sanity check: how big is the address space in a 64-bit system?2) In this class, unless otherwise stated we’ll be using 32-bit systems.

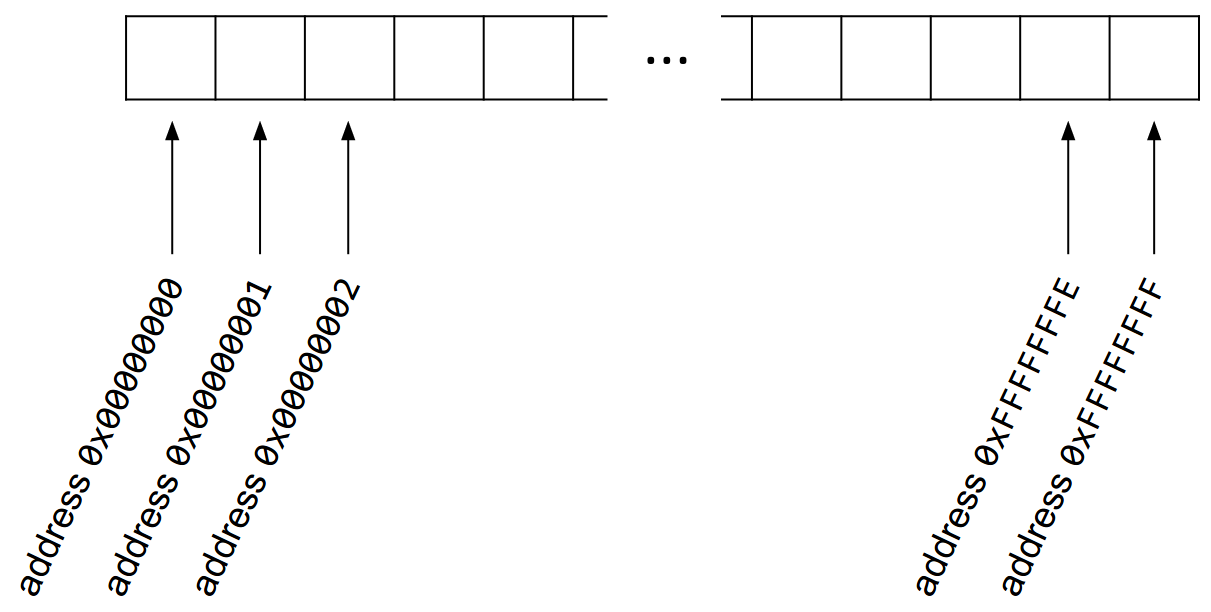

We can draw the memory layout as one long array with \(2^{32}\) elements, where each element is one byte. The leftmost element has address 0x00000000, and the rightmost element has address 0xFFFFFFFF.3

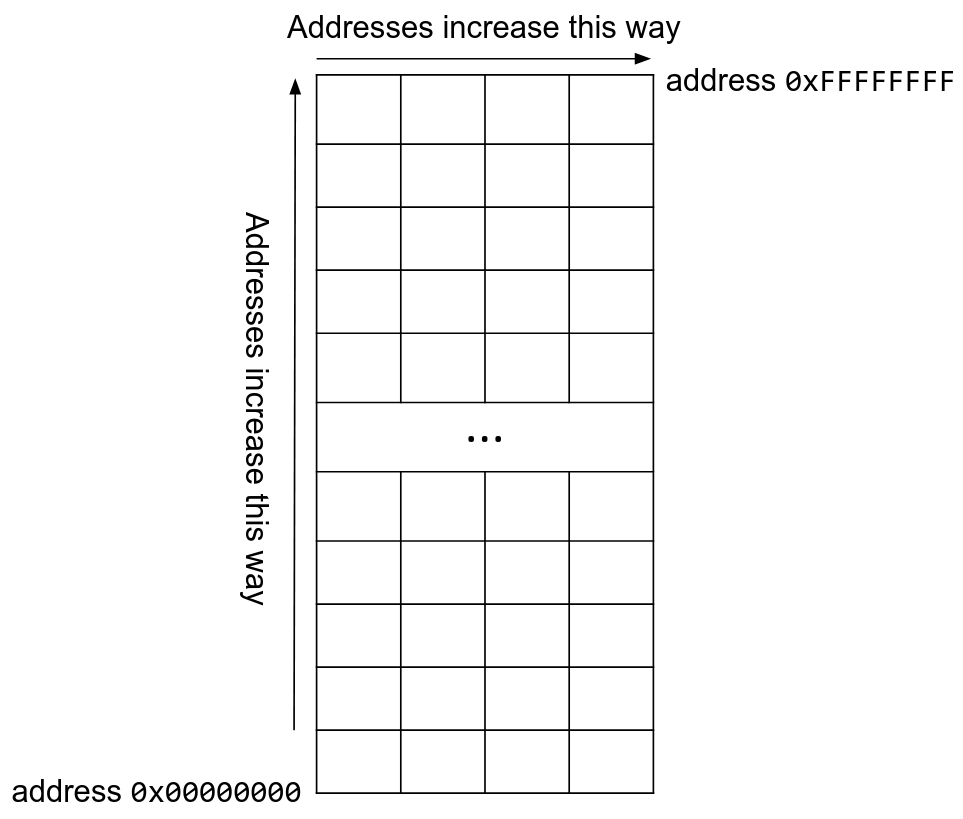

However, this is hard to read, so we usually draw memory as a grid of bytes. In the grid, the bottom-left element has address 0x00000000, and the top-right element has address 0xFFFFFFFF. Addresses increase as you move from left to right and from bottom to top.

Although we can draw memory as a grid with annotations and labels, remember that the program only sees a huge array of raw bytes. It is up to the programmer and the compiler to manipulate this chunk of raw bytes to create objects like variables, pointers, arrays, and structs.

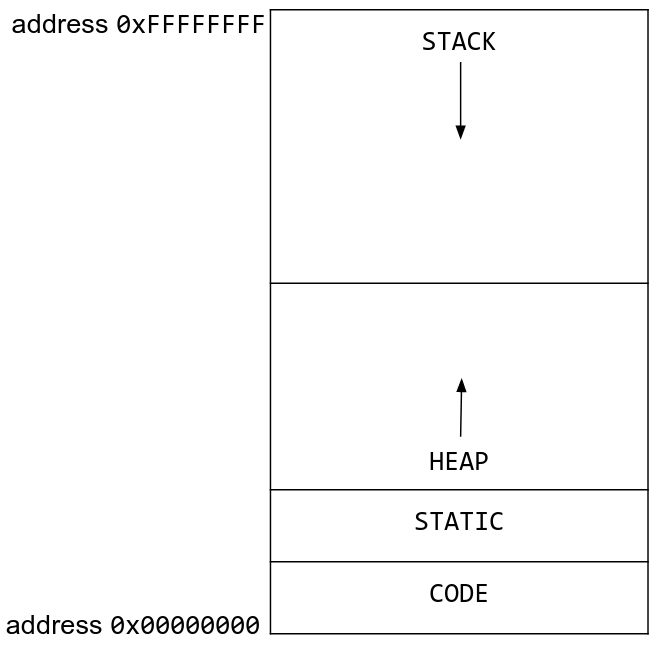

When a program is being run, the address space is divided into four sections. From lowest (smallest) address to highest (largest) address, they are:

- The code section contains the executable instructions of the program (i.e., the code itself). Recall that the assembler and linker output raw bytes that can be interpreted as machine code. These bytes are stored in the code section.

- The static section contains constants, static variables, and global variables.

- The heap stores dynamically allocated data. When you call

mallocin C, memory is allocated on the heap and given to you for use until you callfree. The heap starts at lower addresses and “grows up” to higher addresses as more memory is allocated: older variables will have lower addresses. - The stack stores local variables and other information associated with function calls. The stack starts at higher addresses and “grows down” as more functions are called: older variables will have a higher address. Note that members of a struct are stored with the first member at the lowest address.

Variables can be stored in the heap or in the stack. Since the stack grows down, each new local variable will have a lower address than the previous variables on the stack.

2.4. Little-endian words

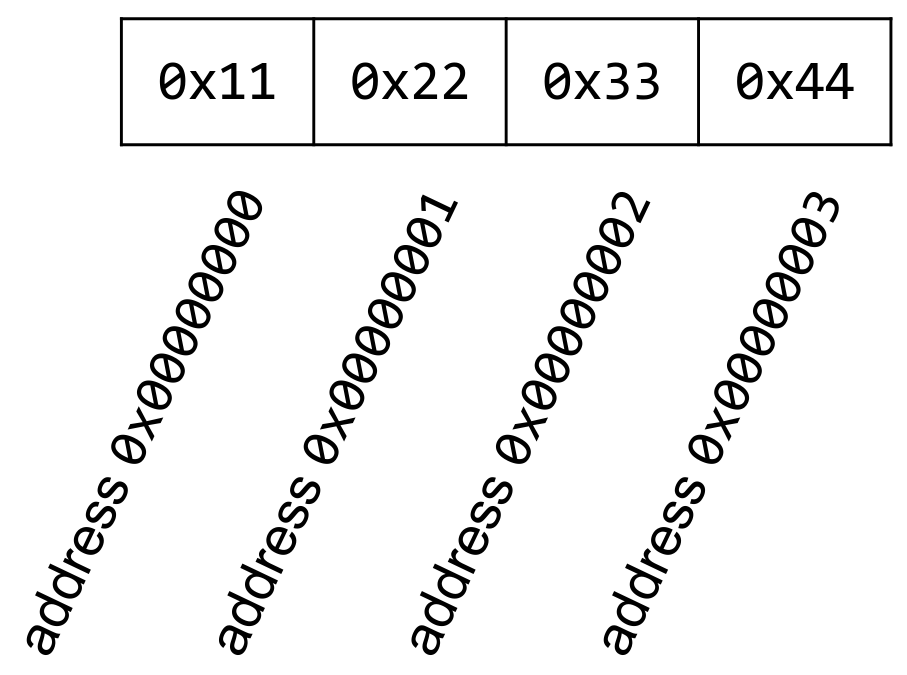

x86 is a little-endian system. This means that when storing a word in memory, the least significant byte is stored at the lowest address, and the most significant byte is stored at the highest address. For example, here we are storing the word 0x44332211 in memory:

Note that the least significant byte 0x11 is stored at the lowest address, and the most significant byte 0x44 is stored at the highest address.

Because we work with words so often, sometimes we will write words on the memory diagram instead of individual bytes. Each word is 4 bytes, so each row of the diagram has exactly one word.

Using words on the diagram lets us abstract away little-endianness when working with memory diagrams. Please remember that the bytes are actually being stored in little-endian format.

As opposed to little-endian words, big-endian words are stored in memory by writing the least significant byte to the highest address. Networking protocols often are big-endian.

2.5. Registers

In addition to the \(2^{32}\) bytes of memory in the address space, there are also registers, which store memory directly on the CPU. Each register can store one word (4 bytes). Unlike memory, registers do not have addresses. Instead, we refer to registers using names. There are three special x86 registers that are relevant for these notes:

- eip is the instruction pointer, and it stores the address of the machine instruction currently being executed. In RISC-V, this register is called the PC (program counter).

- ebp is the base pointer, and it stores the address of the top of the current stack frame. In RISC systems, this register is called the

FP(frame pointer)4. - esp is the stack pointer, and it stores the address of the bottom of the current stack frame. In RISC-V, this register is called the

SP(stack pointer).

The top of the current stack frame is the highest address associated with the current stack frame, and the bottom of the stack frame is the lowest address associated with the current stack frame.

If you’re curious, the e in the register abbreviations stands for “extended” and indicates that we are using a 32-bit system (extended from the original 16-bit systems).

Since the values in these three registers are usually addresses, sometimes we will say that a register points somewhere in memory. This means that the address stored in the register is the address of that location in memory. For example, if we say eip is pointing to 0xDEADBEEF, this means that the eip register is storing the value 0xDEADBEEF, which can be interpreted as an address to refer to a location in memory.

There are 6 other general-purpose x86 registers that we might come accross during this class: eax, ebx, ecx, edx, esi and edi. You do not need to know anything else about these registers for this class.

Sanity check: Which section of C memory (code, static, heap, stack) do eip, ebp and esp registers usually point to?5

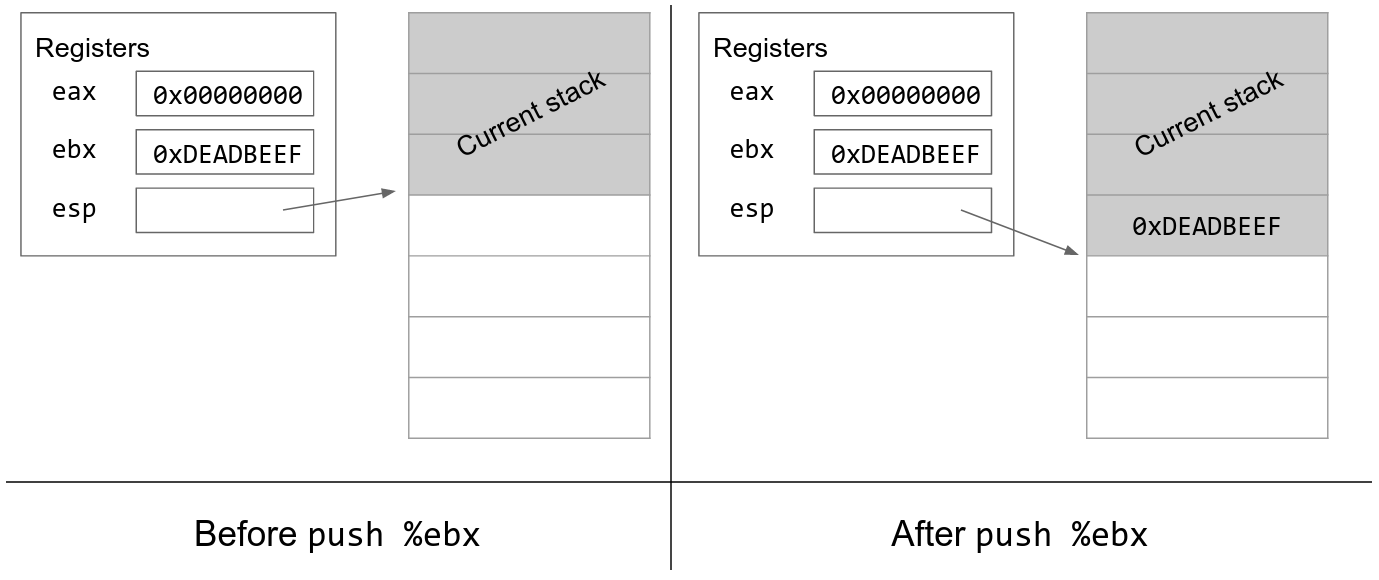

2.6. Stack: Pushing and popping

Sometimes we want to remember a value by saving it on the stack. There are two steps to storing a value on the stack. First, we have to allocate additional space on the stack by decrementing esp. Then, we store the value in the newly allocated space. The x86 push instruction does both of these steps to store a value to the stack.

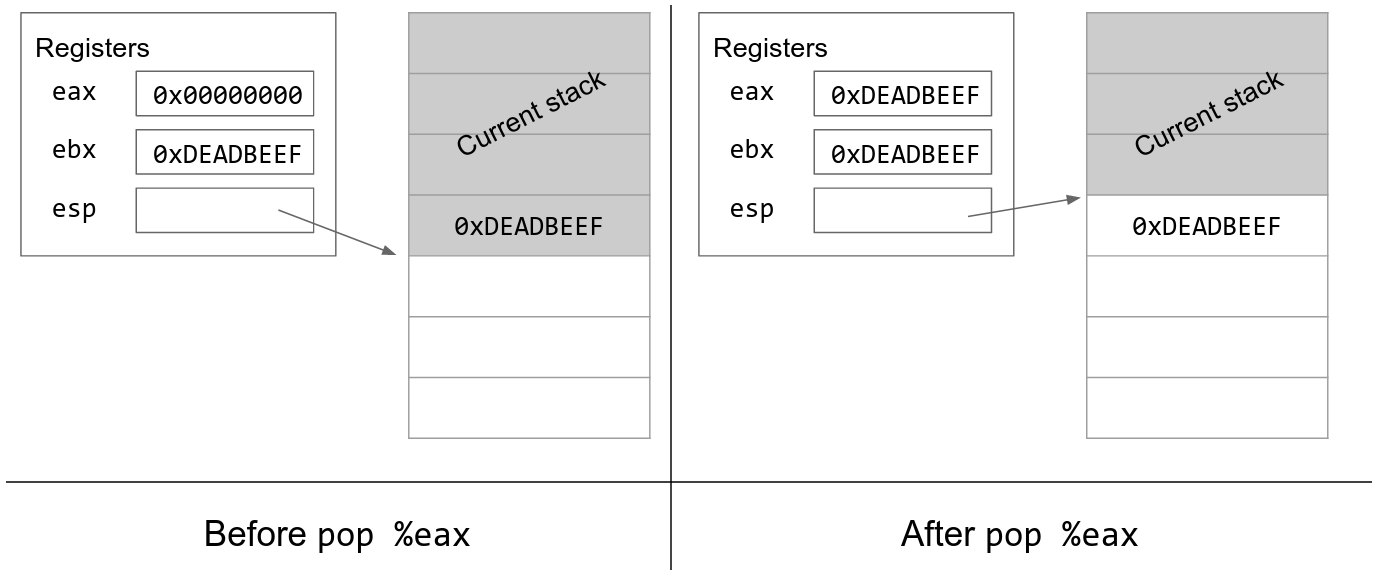

We may also want to remove values from the stack. The x86 pop instruction increments esp to remove the next value on the stack. It also takes the value that was just popped and copies the value into a register.

Note that when we pop a value off the stack, the value is erased from memory. However, we increment esp so that the popped value is now below esp. The esp register points to the bottom of the stack, so the popped value below esp is now in undefined memory.

2.7. x86 calling convention

Instructions are composed of an opcode and zero or more operands. x86 instructions can be variable length, anywhere from 1 to 16 bytes long. In the instruction addl $0x8, %ebx, the opcode is addl, and both $0x8 and %ebx are operands. Specifically, the source is $0x8, and the destination is %ebx, so in pseudocode this can be read as EBX = EBX + 0x8.

This class uses AT&T x86 syntax (since that is what GDB uses). This means that the destination register comes last. This differs from RISC-V assembly, where the destination register comes first.

References to registers are preceded with a percent sign, so if we wanted to reference eax, we would do so as %eax. Immediates (i.e., constants) are preceded with a dollar sign (i.e. $1, $0x4, etc.). Furthermore, memory references use parenthesis: for example, (%esp) refers to memory at the address contained in ESP. It is also possible to add or subtract a constant to the address: for example, 12(%esp) dereferences memory 12 bytes above the address contained in ESP. If parentheses are used without an immediate offset, the offset can be thought of as an implicit 0.

Suppose our assembly instruction was xorl 4(%esi), %eax; here, the opcode is xorl, the source is 4(%esi), and the destination is %eax. As such, in pseudocode, this can be written as EAX = EAX ^ *(ESI + 4). Since this is a memory reference, we are dereferencing the value 4 bytes above the address stored in ESI.

2.8. x86 function calls

When a function is called, the stack allocates extra space to store local variables and other information relevant to that function. Recall that the stack grows down, so this extra space will be at lower addresses in memory. Once the function returns, the space on the stack is freed up for future function calls. This section explains the steps of a function call in x86.

In a function call, the caller calls the callee. Program execution starts in the caller, moves to the callee as a result of the function call, and then returns to the caller after the function call completes.

When we call a function in x86, we need to update the values in all three registers we’ve discussed:

- eip, the instruction pointer, is initially pointing at the instructions of the caller. It needs to be changed to point to the instructions of the callee.

- ebp and esp initially point to the top and bottom of the caller stack frame, respectively. Both registers need to be updated to point to the top and bottom of a new stack frame for the callee.

When the function returns, we want to restore the old values in the registers so that we can go back to executing the caller. When we update the value of a register, we need to save its old value on the stack so we can restore the old value after the function returns.

There are 11 steps to calling an x86 function and returning. In this example, main is the caller function and foo is the callee function. In other words, we are describing what happens when main calls the foo function.

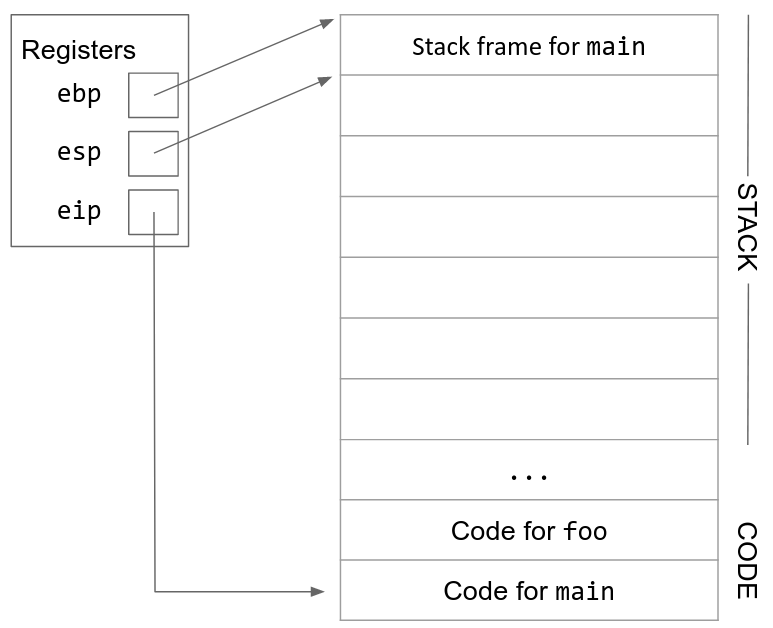

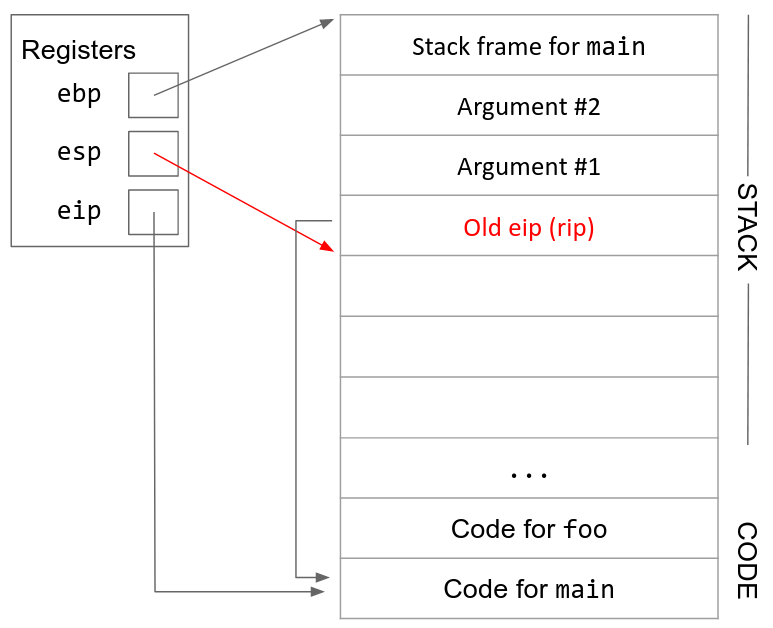

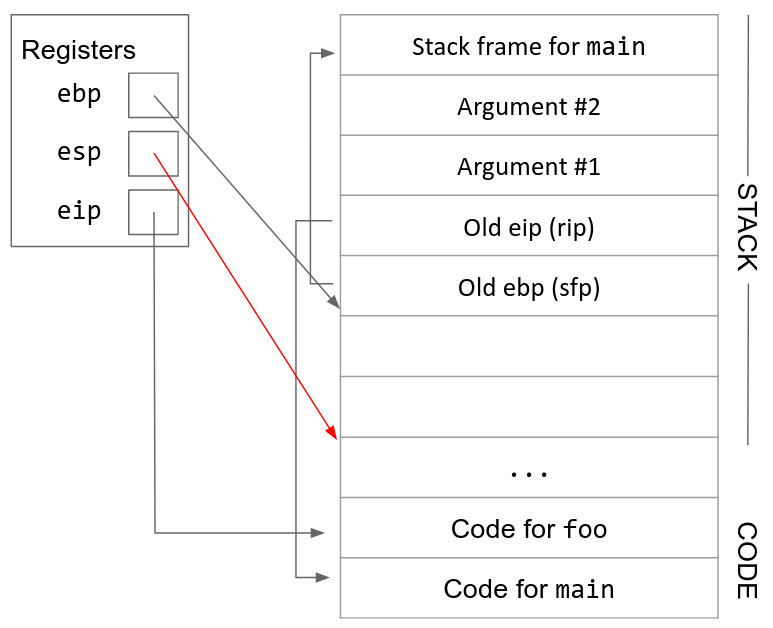

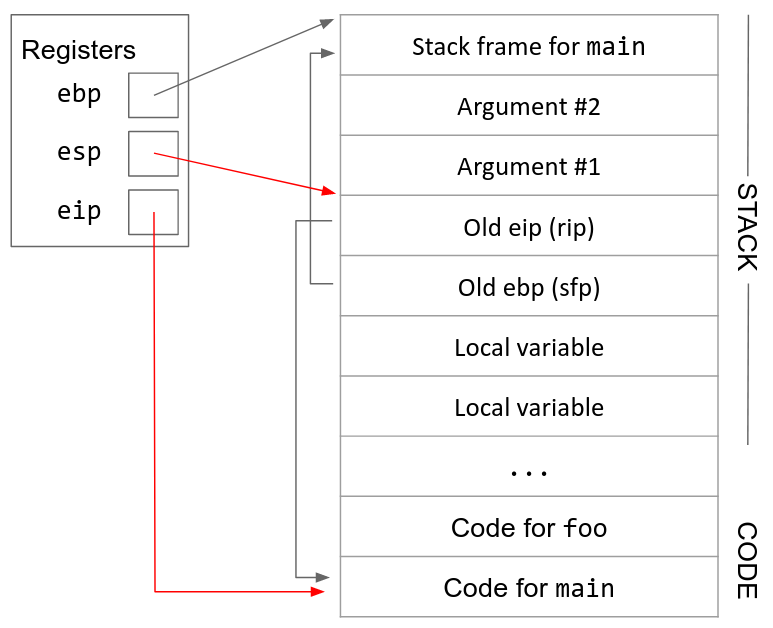

Here is the stack before the function foo is called. ebp and esp point to the top and bottom of the caller stack frame.

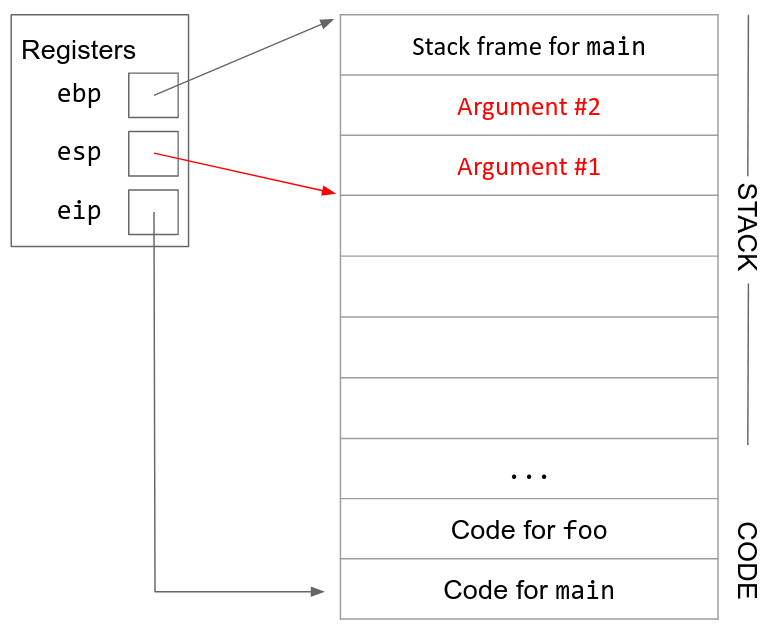

1. Push arguments onto the stack. x86 passes arguments by pushing them onto the stack. (This is different from RISC-V, which passes arguments by storing them in registers.) esp is decremented as we push arguments onto the stack. Arguments are pushed onto the stack in reverse order, so the first argument has the lowest (smallest) address and the last argument has the highest address.

2. Push the old eip (rip) on the stack. We are about to change the value in the eip register, so we need to save its current value on the stack before we overwrite it with a new value. When we push this value on the stack, it is called the old eip or the rip (return instruction pointer).6

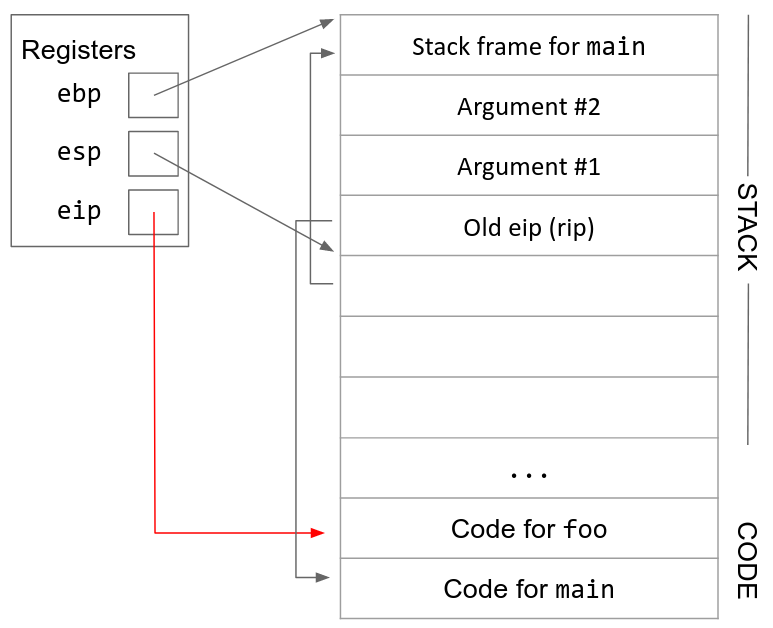

3. Update eip. Now that we’ve saved the old value of eip, we can safely change eip to point to the start of the code of the callee function.

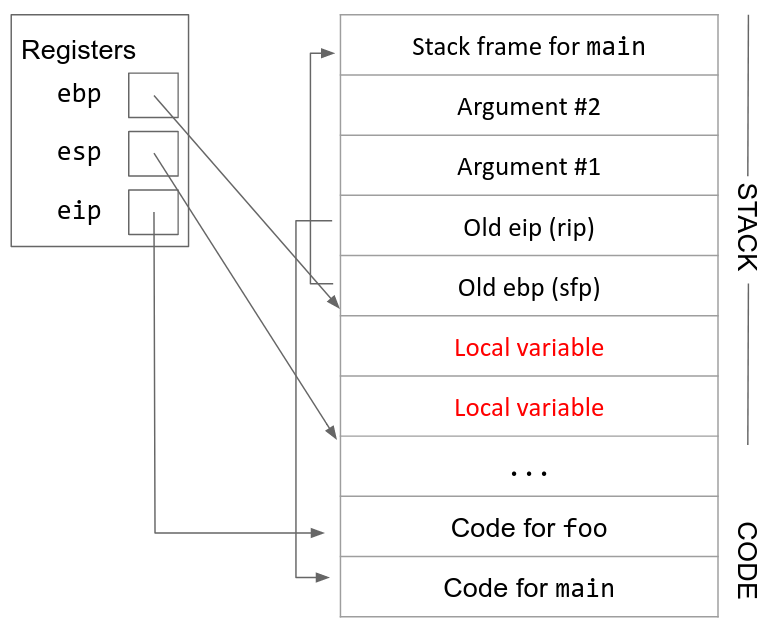

4. Push the old ebp (sfp) on the stack. We are about to change the value in the ebp register, so we need to save its current value on the stack before we overwrite it with a new value. When we push this value on the stack, it is called the old ebp or the sfp (saved frame pointer). esp has been decremented because we pushed a new value on the stack.

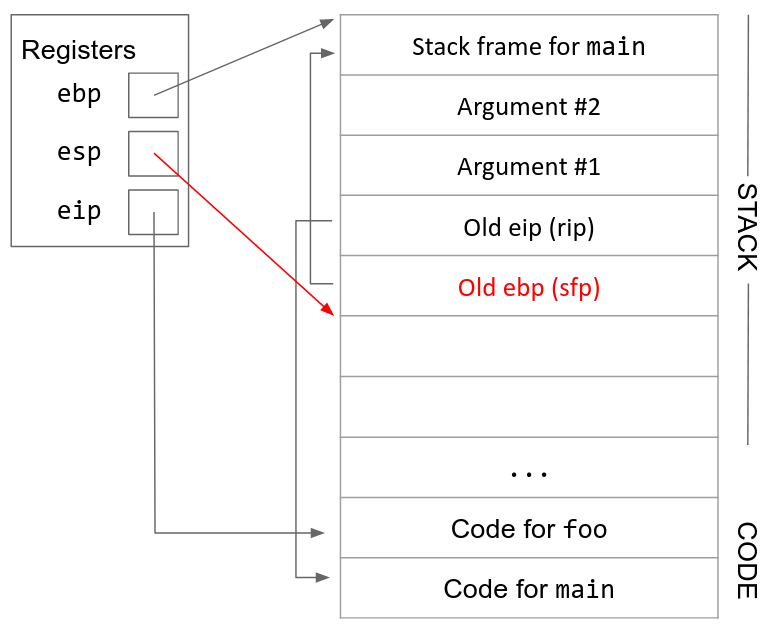

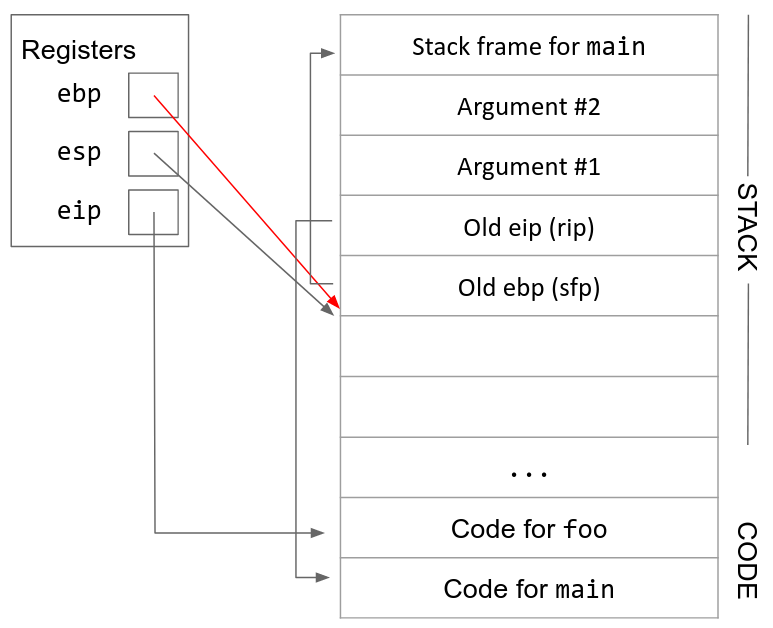

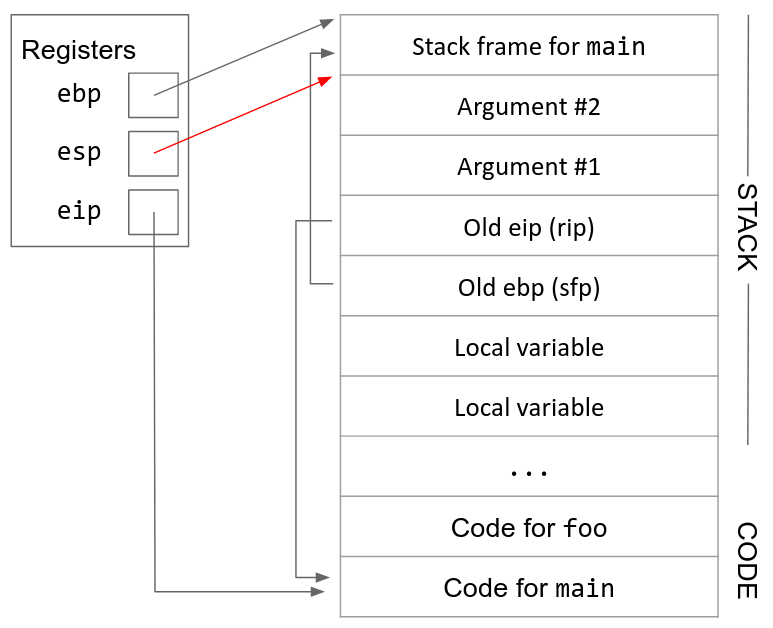

5. Move ebp down. Now that we’ve saved the old value of ebp, we can safely change ebp to point to the top of the new stack frame. The top of the new stack frame is where esp is currently pointing, since we are about to allocate new space below esp for the new stack frame.

6. Move esp down. Now we can allocate new space for the new stack frame by decrementing esp. The compiler looks at the complexity of the function to determine how far esp should be decremented. For example, a function with only a few local variables doesn’t require too much space on the stack, so esp will only be decremented by a few bytes. On the other hand, if a function declares a large array as a local variable, esp will need to be decremented by a lot to fit the array on the stack.

7. Execute the function. Local variables and any other necessary data can now be saved in the new stack frame. Additionally, since ebp is always pointing at the top of the stack frame, we can use it as a point of reference to find other variables on the stack. For example, the arguments will be located starting at the address stored in ebp, plus 8.

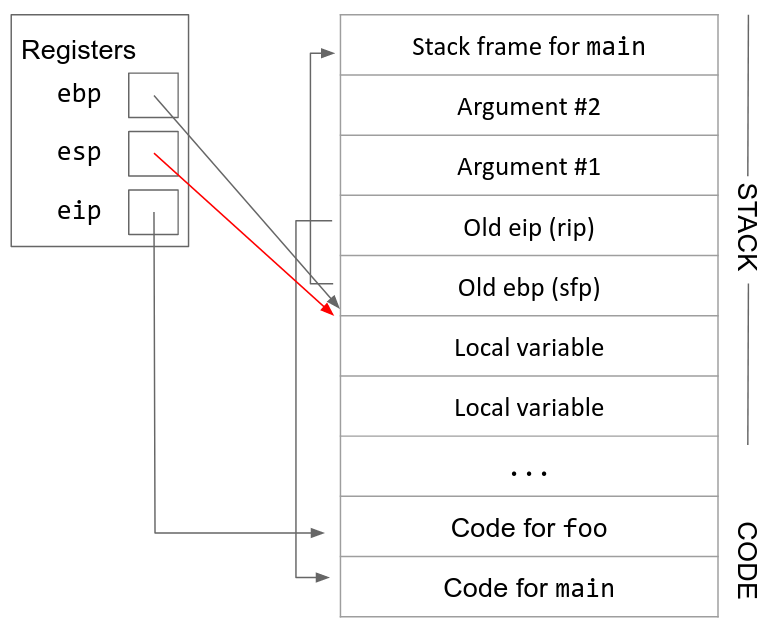

8. Move esp up. Once the function is ready to return, we increment esp to point to the top of the stack frame (ebp). This effectively erases the stack frame, since the stack frame is now located below esp. (Anything on the stack below esp is undefined.)

9. Restore the old ebp (sfp). The next value on the stack is the sfp, the old value of ebp before we started executing the function. We pop the sfp off the stack and store it back into the ebp register. This returns ebp to its old value before the function was called.

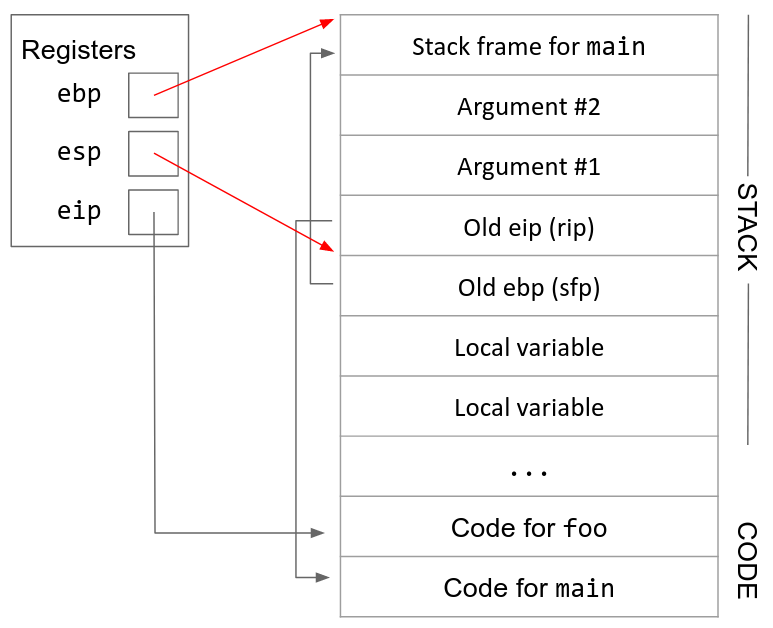

10. Restore the old eip (rip). The next value on the stack is the rip, the old value of eip before we started executing the function. We pop the rip off the stack and store it back into the eip register. This returns eip to its old value before the function was called.7

11. Remove arguments from the stack. Since the function call is over, we don’t need to store the arguments anymore. We remove them by incrementing esp (recall that anything on the stack below esp is undefined).

You might notice that we saved the old values of eip and ebp during the function call, but not the old value of esp. A nice consequence of this function call design is that esp will automatically move to the bottom of the stack as we push values onto the stack and automatically return to its old position as we remove values from the stack. As a result, there is no need to save the old value of esp during the function call.

2.9. x86 function call in assembly

Consider the following C code:

int main(void) {

foo(1, 2);

}

void foo(int a, int b) {

int bar[4];

}

The compiler would turn the foo function call into the following assembly instructions:

main:

# Step 1. Push arguments on the stack in reverse order

push $2

push $1

# Steps 2-3. Save old eip (rip) on the stack and change eip

call foo

# Execution changes to foo now. After returning from foo:

# Step 11: Remove arguments from stack

add $8, %esp

foo:

# Step 4. Push old ebp (sfp) on the stack

push %ebp

# Step 5. Move ebp down to esp

mov %esp, %ebp

# Step 6. Move esp down

sub $16, %esp

# Step 7. Execute the function (omitted here)

# Step 8. Move esp

mov %ebp, %esp

# Step 9. Restore old ebp (sfp)

pop %ebp

# Step 10. Restore old eip (rip)

pop %eip

Note that steps 1–3 happen in the caller function (main). Step 3 is changing the eip to point to the callee function (foo). Once the eip is changed, program execution is now in foo, where steps 4–10 take place. Step 10 is changing the eip to point back to the caller function (main). Once the eip is changed back, program execution is now in main, where step 11 takes place.

The call instruction in steps 2–3 pushes the old eip (rip) onto the stack and then changes eip to point to the instructions for the foo function.

In step 6, esp is moved down by 16 bytes. The number 16 is determined by the compiler depending on the function being called. In this case, the compiler decides 16 bytes are required to fit the local variable and any other data needed for the function to execute.

This class uses AT&T x86 syntax, which means in the mov instruction, the source is the first argument, and the destination is the second argument. For example, step 5, mov %esp, %ebp says to take the value in esp and put it in ebp.8

Since function calls are so common, assembly programmers sometimes use shorthand to write function returns. The two instructions in steps 8 and 9 are sometimes abbreviated as the leave instruction, and the instruction in step 10 is sometimes abbreviated as the ret instruction. This lets x86 programmers simply write “leave ret” after each function.

Steps 4-6 are sometimes called the function prologue, since they must appear at the start of the assembly code of any C function. Similarly, steps 8-10 are sometimes called the function epilogue.

Past Exam Questions

Here we’ve compiled a list of past exam questions that cover x86. These do require an understanding of memory safety vulnerabilities as well, so we recommend understanding those questions first before coming back to these.

-

Answer: Using the table to look up each sequence of 4 bits, we get

0xC161. ↩ -

Answer: \(2^{64}\) bytes. ↩

-

In reality your program may not have all this memory, but the operating system gives the program the illusion that it has access to all this memory. Refer to the virtual memory unit in CS 61C or take CS 162 to learn more. ↩

-

RISC systems often omit this register because it is not necessary with the RISC stack design. For example, in RISC-V,

FPis sometimes renameds0and used as a general-purpose register ↩ -

Answer: eip points to the code section, where instructions are stored. ebp and esp point to the stack section. ↩

-

In reality, the value we push on the stack is the current value in eip, incremented by 1 instruction. This is because after the function returns, we want to execute the instruction directly after the instruction eip is currently pointing to. ↩

-

In reality, eip is now pointing at the instruction directly after the old instruction it was pointing to. This lets us continue executing the caller function right after where we left off to call the function. ↩

-

Note that if you are searching for x86 resources online, you may run into Intel syntax, where the source and destination are reversed. Percent signs

%usually mean you’re reading AT&T syntax. ↩